Absence and Presence - Baudelaire, Hopkins, and Egan

Kevin T. McEneaney, Poet

New York

This Lecture was delivered by Kevin McEneaney during the 2015 Hopkins Festival.

Algernon Swinburne had exalted Victor Hugo as semi-divine poet in his Fortnightly Review of L’Année terrible (1872). Praising Hugo’s domestic poems rather than his political poems, Swinburne created a trend for domestic poems in Victorian England. Hugo had been writing domestic poems since at least 1842, for example, “My Two Daughters,” where his daughters are depicted with white carnations trembling in the breeze like butterflies. In his last letter to Robert Bridges, Hopkins ridiculed Swinburne’s latest windy effort, the Armada, as:

a perpetual functioning of genius without truth, feeling, or any adequate matter to be at function on….a blethery bathos into which Hugo and he from opposite coasts have long driven Channel-tunnels.

Amid the forest of sentimental domestic poems in England, Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “To Margaret” remains the finest example of that domestic genre popularized by Hugo.

Swinburne had ignited an explosion of banal, domestic cuteness in England over the next few decades. Poets like Swinburne and Christina Rossetti joined that movement to endow English with the prolix assonance that the French valued so highly. A general tendency in late Victorian poetry encouraged verbose treacle laden with clotted articles. Greek classists, like Thomas Hardy, Gerard Hopkins, and Ezra Pound, reformed the language to a streamlined simplicity more akin to Anglo-Saxon brevity, while at the same time reviving alliteration and eschewing awkward articles, which do not appear in Greek.

While Charles-Pierre Baudelaire was known to his contemporaries more as a journalist and critic, his book of poems Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) enjoyed success as mere scandal. Most of those poems had been composed before the age of twenty-three and subsequent poems like “Correspondences” bear the stamp of Swedenborg’s theological influence. But instead of seeing angelic messengers everywhere in ordinary life, Baudelaire saw demons everywhere.

As a theorist of painting and literature, Baudelaire prized the comic over the tragic, a concept that Patrick Kavanagh later adopted. In translating Edgar Allan Poe into French, Baudelaire perfected his Gothic frisson, which he later extended into his poetry by combining it with etching-like voyeuristic humor deliberately designed to offend bourgeois tastes. Sainte-Beuve ambiguously defended Baudelaire by pointing out that all subjects but evil had been overly written about.

Baudelaire’s perspective on evil, even his posturing Satanism, was hardly anti-Christian, but a critique of Christianity for being humorless. If Baudelaire’s “Satanism” was serious, not a parody of deviant cult mindsets, his poems would not posses their enduring amusement it. Some may regard those poems as adolescent, yet the language is marvelously mature.

In his essay “Of the Essence of Laughter,” Baudelaire complains “that the sage of all sages, the Incarnate Word, has never laughed. In the eyes of Him who knows and can do all things, the comic does not exist. And yet the Incarnate Word did know anger; he even knew tears.” Baudelaire’s acute visual sense of comedy grew out of his affection for pen-and-ink caricature. Ever a Francophile, it was Swinburne who had first championed Baudelaire in England five years after the publication of Les Fleurs du Mal.

In exploring the subject of evil, Baudelaire emphasized the abject distance of man from God, an appropriate theme for a sardonic pessimist. Gustave Flaubert’s reaction to Baudelaire’s Les Paradises Artificial (1860) was that this later volume harped too much on the “spirit of Evil.” Baudelaire replied that he had:

always been obsessed by the impossibility of understanding certain of man’s thoughts or deeds, unless we accept the hypothesis that an evil force, external to man, has intervened. Now that’s a great admission that the whole of the nineteenth century couldn’t conspire to make me blush at. Note well that I’m not going to renounce the pleasure of changing my mind or contradicting myself.

Baudelaire’s line between line between comedy and evil was an autobiographical self-lacerating Christian guilt. At bottom, Baudelaire was deeply and opaquely Pauline; perhaps Baudelaire even suffered from bipolar disorder. Whether he contracted syphilis, gonorrhea, or sexual herpes still stirs debate. Whatever the case, it was a traumatic illness that veered him into a Jansenistic view of sex, perceiving sex as a vicious malady. Some of his friends even thought he died a virgin. While the damned narrators of his poems owe a deep debt to Poe (who conceptually imitated the monologues of Dante Alighieri from Inferno), Baudelaire’s portraits and his Satanic monologues, remain rooted in exaggerations of caricature—they satirize what they portray.

Baudelaire’s philosophy was dualist, Manichean; his primary experience was an aesthetic horror of life: disgust with ignorance, prejudice, the small-minded thinking that he found excruciatingly boring. Except for a few friends like his muse Apollonie Sabatier, Flaubert, Saint-Beuve, Caroline Aupick, Theophile Gautier, and, above all, the great love of his life—his mother—Baudelaire could tolerate conversation with only a few people. Like E.T.A. Hoffmann, Baudelaire elevated Horror into a comic aesthetic: laughter is the voice of “the fallen angel who remembers the heavens.” The effects and products of the Fall become the means for redemption, ensuring a regenerative force. In Rabelais and His World Mikhail Bakhtin had claimed a somewhat similar vitality in the satiric dialectic of Carnival, yet Baudelaire’s social outlook perceived only unremitting horror, a grinding drama of Gothic sensationalism in poems where the crescendo underwent no reversal, perfecting in poems like L’horloge (The Clock) what he had learned in translating Poe’s “The Raven.” Such was the aesthetic Joseph Conrad would later incorporate into his novella on colonial horror, The Heart of Darkness (1899).

Baudelaire’s laughter dovetails the secular and theological in a mystic plane of Swedenborgian correspondences. Such heaven/hell dualism includes what it mocks: momentarily transcending dualism in ecstasy ensures that the norm remains: the satirist can never escape his subjective paradox of feelings, yet romantically yearns to do so; that is, the satirist exhibits the fallen state of exile, despairing hope—which remains a comic absurdity—a concept that Albert Camus would later develop in vivid existential detail.

Both Baudelaire and Hopkins possess linkage to the visual arts. While Baudelaire was a critic of painting, caricature, and sculpture, Hopkins remained a draftsman of nature under the influence of Ruskin. Baudelaire, like other symbolists, was rooted in atmosphere, while Hopkins was rooted in the imagistic line coupled with Greek concision, logical thought, and religious mysticism.

By mid-May, 1867, Hopkins had decided to join the Jesuits, leaving his parents ignorant of his decision. His old Hampstead neighbor friend Edward Bond, who had attended St. John’s College at Oxford, and with whom at home he had read Tacitus and Virgil’s Georgics were off to Switzerland and France in August of 1868 for a little tour because once Hopkins joined the Jesuits, he would be forbidden to enter France.

Hopkins and Bond traveled down the Rhone and climbed the Wylerhorn: in his Journal Hopkins notes: “Firs very tall, with the swell of the branching on the outer side of the slope so that the peaks seem to point inwards to the mountain peak, like the lines of the Parthenon, and the outline melodious and moving on many focuses.” Hopkins describes the cascading falls of Mount Reichenbach as “inscaped in fretted falling vandykes in each of which the frets or points, just like the startings of a just-lit Lucifer-match, keep shooting in races, one beyond the other, to the bottom.” Unlike Chateaubriand or Shelley, Hopkins makes no attempt to find romantic symbolism in the landscape. He sketches the landscape in terms of history, architecture, and mystical inscape.

Bond and Hopkins hopped on a train to Paris where Bond—whose interest in poetry was more secular than religious—might have been aware that Baudelaire had died the previous August on the 31st of the month, 1867. Yet if Bond mentioned Baudelaire while they changed trains in Paris on August 1st, Hopkins would have had no interest in Gothic poetry, which in the main had been a sinkhole of mediocrity with the singular exception of Baudelaire.

Norman White notes briefly the thematic similarity of Hopkins’ “To his Watch” with Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury’s “To his watch, when he could not sleep,” as well as Baudelaire’s “L’horloge,” (The Clock). We cannot ever know if Hopkins’ uncompleted draft was abandoned or merely misplaced and forgotten, since the latter (I can attest) often occurs in the writing of poetry. Dating Hopkins’ poem to 1885, White speaks eloquently of Hopkins’ initial confusion and subsequent, bleak despair on arriving in Dublin. White declares the topic of clock and time to be “a strange misjudgment” on the part of Hopkins and “a lazy unpropitious choice.” Yet this scenario could have also been writer’s block, or the poem abandoned for reasons of piety because of its obviously ambitious narcissism. Dismissing any pre-emptive judgments, and noting that Herbert’s watch poem (which begins with the same title as Hopkins’s sonnet) in three quatrains contains a reversal (while Baudelaire’s, predictably, does not), Herbert’s reversal being remarkably similar to John Donne’s “Death be not proud” sonnet. I have attempted to complete Hopkins’ sonnet with appropriate imagery and traditional reversal:

To his Watch

MORTAL my mate, bearing my rock-a-heart

Warm beat with cold beat company, shall I

Earlier or you fail at our forge, and lie

The ruins of, rifled, once a world of art?

The telling time our task is; time’s some part,

Not all, but we were framed to fail and die—

One spell and well that one. There, ah thereby

Is comfort’s carol of all or woe’s worst smart.

Field-flown, the departed day no morning brings

Saying ‘This was yours’ with her, but new one, worse,

And then that last and shortest day of the year

before a circular encompassing sings

the redemptive song defeating Adam’s curse

that good news all weary men are glad to hear!

Mariani’s 1970 commentary interprets shortest as referring to the day of personal death, yet shortest might also refer to the shortest day of the calendar year with its exfoliating optimism: Christmas, Redemption, Christian good news. White had merely echoed Mariani’s earlier pessimism, neither considering the sonnet’s reversal convention nor the telling foreshadowing of the phrase “comfort’s carol.”

“As kingfishers catch fire” presents the bird as a symbol of the “all-pervasive presence of Christ and the fundamental need of dedicating all that men do to God.” The bird in Baudelaire’s “The Albatross” becomes a symbol of the poet pinned to the deck of a ship amid a jeering, mocking crew. Both Baudelaire and Hopkins invest a bird with sociological mythology: Baudelaire’s grounded bird being secular, Hopkins’ aerial flight limning religious justice and joy.

Let me conclude this dialectic of pessimism and hope, absence and presence, Baudelaire and Hopkins, with a contemporary poem. Desmond Egan’s “Halcyon” mediates aspects of both Hopkins and Baudelaire. Halcyon is the technical name of the woodland kingfisher’s genus who, according to ancient Greek legend, was thought to nest at sea during the winter solstice, calming the ocean while nesting. Kingfishers are notoriously shy birds and even in Egan’s tone he aptly captures this quality. It should be noted that kingfishers in these neighboring isles continue to remain under threat of extinction.

Written with informal tone rather than formal Baudelairian language, Egan paints—as in a watercolor, rather than Hopkins-like sketch—a kingfisher catching a writer unexpectedly. Overawed, he concludes that “all our indoor words” about Hopkins, theology, and beauty remain inadequate to the revelation of beauty and grace in the flesh.

The trajectory of the poem segues from nature to the human, something Egan has observed in his analysis of Hopkins’ Kingfisher poem. As in Baudelaire’s “The Albatross,” the bird becomes identified with the poet “ready to plunge at the unsafe / through the imaginary skin.” The authorial mask wonders why revelation has occurred at this moment as meditation descends to self-recriminatory guilt, for at the moment of revelation; the grounded author had despaired of discovering beauty. Citing Hopkins and St. Paul in an essay, Egan has noted that suffering “affords the possibility to advance in love,” i.e., suffering is a nesting period. “Halcyon” concludes with a humble via negativa prayer, a prayer for retaining the Christian-incarnated grace cited in Hopkins’ Kingfisher poem:

bring fiercely together something that wants to but cannot

The poem’s theme of presence/absence acknowledges that temporary hiatus between inspiration and will. The nesting stillness of the poem’s conclusion functions as a refutation of T.S. Eliot’s Burnt Norton IV: “After the kingfisher's wing / Has answered light to light, and is silent, the light is still / At the still point of the turning world.” Egan perceives that Archimedean still point as prayer itself, rather than Eliot’s secular Keats-like conceit of a motionless Chinese rose jar moving in stillness. Egan’s prayerful conclusion echoes Hopkins’s late “Justus quidem” poem with its devout plea “send my roots rain.”

Egan, who began his poem with a flash of Hopkins-like color, explicitly notes the symbolic inscape of the kingfisher scattering “airwards / blurring into symbol,” then demythologizes the event to the ordinary-personal where myth becomes an inscape phenomenon of nature. The suggestion of being hunted (“hunt me”) by the symbolic kingfisher pointedly evokes Francis Thompson’s poem “The Hound of Heaven.” The speaker aspires to catch fire and grace, then is surprised by guilt after joyful recognition, thus appropriating Hopkins’ theme of the poet’s role: “for that I came.” Our 21st century is more complex, less Manichean than the 19th century, less public, more private, as well as more daringly oblique in the way we construct postmodern art.

Baudelaire’s poem extracts cathartic pity for the social predicament of the poet; Hopkins’ sonnet on the kingfisher expresses forceful optimism built upon incarnational imagery; Egan’s darting lyric lines reflect the more personal and ambiguous world of the poet’s nesting situation as a postmodern artifact straddling the world of literature and religion: aspiring to fly like the kingfisher, yet more commonly ensnared like the albatross. Baudelaire dramatizes the social plight of the poet; Hopkins transforms the poet’s role into religious fervor; Egan focuses on the wrestling process of creativity supplemented by grace. The struggling agon of Egan’s luminous poem presents the figura of the writer revived in turquoise imagery and imagination. While Egan’s poem remains less optimistic than Hopkins’ Kingfisher poem, Egan’s dark-night-of-the-soul Christian vision presents a more calming and centered optimism than the broadly comic sadomasochism of Baudelaire’s sociological caricature in “The Albatross.”

Notes

Swinburne, A., “L’Année terrible,” Fortnightly Review, vol. 12. For an excellent discussion of Hugo’s reputation in England see Hooker, Kenneth War, The Fortunes of Victor Hugo in England (New York: Columbia University Press, 1938.

“My Two Daughters” Guest, Harry, trans., The Distance, the Shadow (London: Anvil Press Poetry, 1981), 74.

Abbott, Claude Colleer, ed., The Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Bridges (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1955), 304.

Williams, Roger L., The Horror of Life (London: Weindenfeld & Nicolsen, 1980), 17. Verlaine employs the phrase “l’horreur de vivre” in his Baudelaire-inflected poem as he recalls his affair with Rimbaud in the sonnet “Luxures” from Jadis et Naguère (“Once and a Long Time Ago”), 1884.

Baudelaire: Selected Writings on Art and Artists, trans. P. E. Charvet (London: Penguin Books, 1972), 142.

Baudelaire, Lloyd, Rosemary, trans., Selected letters of Charles Baudelaire: The Conquest of Solitude (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1986), 197. Swinburne’s review appeared in the Spectator.

Cited by Hannoosh, Michael, Baudelaire and Caricature (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1980), 20.

Schneider, Elizabeth W., The Dragon in the Gate (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968), 11-12.

Phillips, Catherine, ed., Gerard Manley Hopkins: The Major Works (Oxford: Oxford World Classics, 1986), 193.

Swinburne’s famous elegy on Baudelaire, Ave atque Vale (198 lines), was written in 1866, the year before Baudelaire died.

When He Could Not Sleep Uncessant Minutes, whil’st you move you tell

The time that tells our life, which though it run

Never so fast or farr, you’r new begun

Short steps shall overtake; for though life well

May scape his own Account, it shall not yours,

You are Death’s Auditors, that both divide

And summ what ere that life inspir’d endures

Past a beginning, and through you we bide

The doom of Fate, whose unrecall’d Decree

You date, bring, execute; making what’s new

Ill and good, old, for as we die in you,

You die in Time, Time in Eternity.

Text of “To his Watch” from the Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970, 4th edition with this note: On a sheet by itself; apparently a fair copy with corrections embodied in this text, except that the original 8th line, which is not deleted, is preferred to the alternative suggestion, Is sweetest comfort’s carol or worst woe’s smart. My speculative completing of the poem appears in blue ink.

Mariani, Paul, A Commentary on the Complete Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins (Ithaka: Cornell University Press, 1970), 261.

Phillips, Catherine, Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Victorian Visual World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 242.

Weary sailors, merely for amusement, sometimes

Snare an albatross, that enormous sky-bird

Who indolently trails and circles

Spray-tossed ships across oceans.

Hardly has it been yanked down to deck

When this lord of azure, anxiously, clumsily,

Begins to flap, abortively, its huge white wings,

Scraping oak boards like a broken oar.

The weak wanderer, so serene and graceful,

Is now awkward, hobbled, lame, comic!

A prankster crams a pipe into its beak,

Another mimics the cripple who once soared!

The poet is just like this prince of clouds

Who glides the tempest, mocking the archer,

Cut off from sunlight, the mob jeering loud,

His anguished elbow-wings pinned to paper!

—Charles-Pierre Baudelaire, (translated by Kevin T. McEneaney)

Egan, Desmond, Hopkins in Kildare (Newbridge: The Goldsmith Press, 2012), 20:

Halcyon

a dart of turquoise

so deep so small small to

background everything

with the weed river

yes

you caught me

cutting below the aqueduct

that Hopkins day

so other

such an air of outside after

all our indoor words

yet hardly belonging to the fields

to water neither

ready to plunge at the unsafe

through the imaginary skin

and scatter your way airwards

blurring into symbol

but why did you

who show to few

come there then just

following what ley line

and why why should you

I had forgotten the very

urge hunt me since

bring fiercely together

something that wants to but

cannot

Eliot, T.S., “Burnt Norton, IV” The Complete Poems and Plays (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1952), 121.

Lectures from GM HOPKINS FESTIVAL 2023

- Vision and perception in GM Hopkins’s ‘The peacock’s eye’ Katarzyna Stefanowicz

- Hopkins Trees and Birds Margaret Ellsberg

- Joyce, Newman and Hopkins : Desmond Egan

- Joyce's friend, Jacques Mercanton has recorded that he regarded Newman as ‘the greatest of English prose writers

’. Mercanton adds that Joyce spoke excitedly about an article that had just appeared in The Irish Times and had to do with the University of Dublin, “sanctified’ by Cardinal Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins and himself.

Read more ...

- Hopkins and Death Eamon Kiernan

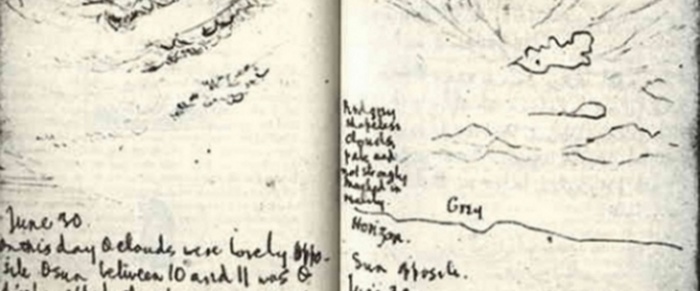

Gerard Manley Hopkins’s diary entries from his early Oxford years are a medley of poems, fragments of poems or prose texts but also sketches of natural phenomena or architectural (mostly gothic) features. In a letter to Alexander Baillie written around the time of composition He was planning to follow in the footsteps of the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who had been known for writing poetry alongside painting pictures ... Read more

Margaret Ellsberg discusses Hopkins's connection with trees and birds, and how in everything he wrote, he associates wild things with a state of rejuvenation. In a letter to Robert Bridges in 1881 about his poem “Inversnaid,” he says “there’s something, if I could only seize it, on the decline of wild nature.” It turns out that Hopkins himself--eye-witness accounts to the contrary notwithstanding--was rather wild. Read more

-An abiding fascination with death can be identified in the writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Easily taken for a sign of pathological morbidity, the poet's interest in death can also be read more positively as indicating, his strong awareness of a fundamental human challenge and his deployment of his intellectual and artistic gifts to try to meet it. Hopkins's understanding of death is apocalyptic. ... As will be shown, apocalyptic thought reaches beyond temporal finality. Hopkins's apocalyptic view of death shows itself with perhaps the greatest consequence in those few works which make the actual event of death a primary concern and which, moreover, leave in place the ordinariness of dying, as opposed to portrayals of the exceptional deaths of saints and martyrs. Read more

Lectures from Hopkins Literary Festival July 2022

- Landscape in Hopkins and Egan Poetry Giuseppe Serpillo

- Walt Whitman and Hopkins Poetry Desmond Egan

- Emily Dickenson and Hopkins Poetry Brett Millier

- Dualism in Hopkins Brendan Staunton SJ

Hopkins's Manuscript Notebook

Lectures delivered at the Hopkins Literary Festival since 1987

© 2024 A Not for Profit Limited Company reg. no. 268039