Hopkins and Simile

Something happens when verse becomes poetry: a blank look become alive, muscles contract, the senses awaken, everything is forgotten, nothing else matters, except that page open before us or those sounds from a human voice.

Giuseppe Serpillo,University of Sassari,

Sardinia

Not everything Hopkins wrote is of great quality. He was aware of this, as he was of the high quality of some of his best pieces. His repudiation of so much of his early production was probably due, not just to religious scruples, but especially to his awareness that most of it was verse, not poetry.

Yet it is not easy to say: `This is mediocre' when discussing Hopkins: it sounds like profanation. Besides, if you start making distinctions between what is good or bad poetry, there will immediately be someone asking you the crucial question: `Very well, but what is poetry?' Sidney, Shelley, Wordsworth

and a thousand others have already tried to answer that most dismal question: I cannot add much to what they have said.

Yet something does happen to us when verse becomes poetry: dull eyes, a blank look become alive, muscles contract, the senses awaken, everything is forgotten, nothing else matters, except that page open before us or those sounds from a human voice which seem to flow independently of the individual uttering them. Coleridge'

s `esemplastic power!' Everything clears up, fits into place: not one useless detail, no punctuation mark one would like to change or drop. Critical thinking comes later: the disjecta membra of the piece which has been enjoyed as a whole are inspected, analyzed, compared: the critical mind tries to find reasons, explanations to what has already been caught instinctively through one's sense of beauty!

However, one's insight and sense of beauty are not metaphysical qualities: they also depend largely on the aesthetic theories current at the time of composition and/or the verbal reproduction of the literary piece: they create expectations within a frame of mind which supports not only our idea of what poetry is or should be, but indeed our whole world view. Our natural perception of beauty and perfection needs this critical framework, which will give it its shape and will prevent it from disappearing quickly into an indistinct universe of volatile emotions.

The Metaphor and Simile

Everybody will agree on this, that in poetry, the theme and its formal linguistic-rhetorical pattern are so closely related that any choice regarding the code system will have a crucial effect on the reader's response. If it is true that no great poetry will ever be produced by anybody lacking in emotional responsiveness and moral sensibility or an awareness of the complex architecture of the universe, all of these qualities will not result in a satisfactory aesthetic product unless they are filtered through the sieve of an adequate verbal style. A mature poet, of course, is likely to make the right choice, yet even a good poet may, at times, fail; in like manner, a young poet may occasionally find the perfect point of coincidence between his message and his medium and produce a perfect piece of poetry.

On the other hand, some aspects of style are conventionally seen as more adequate than others. Every age has its favourite poetic diction, but there seem to be modes of verbal communication which have always been considered as intrinsically more typical of poetry than others; if you just consider some of the most frequent figures of speech and of thought - metaphor and simile for example - the former rather than the latter has been considered as more typical of the poetic language; instead, simile has often been seen as being more able to help express the logical qualities of the mind.

When a critic like Robert Boyle declares, and demonstrates, that Hopkins's mind tends towards expression through metaphor rather than through simile , he is not stating a simple fact: he is making an aesthetic judgement on Hopkins' poetry. He is saying: here, this is great poetry, because its author has succeeded - all the time and coherently - in resorting to the best, most direct way of producing poetry: metaphor. Boyle gives little attention to simile in Hopkins. I believe this is not due to the fact that Hopkins does not use simile too often - he does, if not with the same frequency as metaphor - but to Boyle's implicit feeling that simile is so much less `poetic' than metaphor: To a mind which prefers the clarity and order of concept - he informs us - simile is the natural expression. To a mind which hungers for the reality of being, even involved as being is in the darkness of unintelligibility, mystery, and confusion, metaphor is the natural expression .

Clearly, Boyle

discovers in metaphor the creative force of `imagination' and in simile the milder one of `fancy' . For him, Simile deals with relation between beings, not directly with being itself. Hence, since the two sides of the simile both exist outside the mind, simile can be used by the scientist .

Is there a covert contempt for simile in this definition, a suggestion that no simile will ever produce the prodigiously aesthetic and psychological effects of metaphor? Maybe not; perhaps he just takes for granted that metaphor has a wider range of applications so that discussing simile may not be worth the effort. What I will try to demonstrate in this article is that Hopkins's use of simile through the years is so qly related to the growing complexity of his soul that, while one could easily endorse Boyle's definitions of simile - simile can be used to clarify. Simile is available to scientists' - when discussing Hopkins's early poetry and some of his fragments, those definitions are no longer tenable for his mature poetry. Indeed, his struggle with words, - which I discussed a few years ago - is made specially visible by his long efforts to come to terms with this figure of speech, to mould its `logical' structure so that it suits his expressive needs. In other words, when some of Hopkins' verse does not rise above mediocrity, that is not due to a prevalence of simile over metaphor but to other reasons, among them an inadequate mastery of this figure of speech, which is perhaps more difficult to use creatively than metaphor itself, or to an unrestrained flow of q sentiments not yet wholly mastered or still unmastered by a mature style.

All these variables appear or re-appear at different times in the course of his poetic career, and this might account for the great number of fragments which have reached us and still puzzle us. It is a fact, however, that fewer and fewer similes are to be found in his late production; yet, when they are, it is clear that they turn out to be much more complicated structures than is usually propounded, as Hopkins takes on a point of view which allows him to concentrate on the so-called `tertium comparationis', that is the features, traits, properties which the terms of a comparison have in common .

The Maturing of Hopkins

It will be necessary to distinguish between Hopkins's early experiments and fragments on the one hand, and his more mature output on the other. Simile will tell us different stories in the former and in the latter. Similes are certainly more frequently used in the poems written before 1876: through them we are given a glimpse, to paraphrase Leech, into a mind stretched to explore and understand but also into the emotions and feelings of a young poet still unable to control their free flow through the mastery of language and style. In A fragment of anything you like, probably written when he was eighteen, simile is the device through which the poet tries to spell out impressions or images which seem always on the point of escaping his control. The final result of his quest, as indicated by the title itself, is `fragmentary':

Fair, but of fairness as a vision dream'd

Dry were her sad eyes that would fain have stream'd;

She stood before a light not hers, and seem'd

The lorn Moon, pale with piteous dismay,

Who rising late had miss'd her painful way

In wandering until broad light of day;

Then was discover'd in the pathless sky

White-faced, as one in sad assay to fly

Who asks not life but only place to die.

Il Mystico, a fragment of 140 lines, written when he was the same age, offers five similes, one of them extended; that is, as many as can be found in The Wreck of the Deutschland, 280 lines. A Vision of the Mermaids written a few months later, is stuffed with at least eight similes, all in 143 lines; `The Windhover', Pied Beauty, The Caged Skylark, instead, all have one simile.

In A Vision of the Mermaids, we have an interesting sample of the sort of imagery the use of similes was able to produce at that time and an indication of the sort of emotional disposition which produced it. The speaking voice informs us that rowing, (he) reach'd a rock... at the setting of the day. Here, in absolute peace and stillness, he has a vision of beauty, represented by mermaids six or seven. Before they actually rise from the sea, the beholder says he has admired `an isle of roses' and after it other such small islands in shoals of bloom. The simile which follows is elaborate and gives the reader an idea of effort:

... as in unpeopled skies,

Save by two stars, more crowding lights arise,

And planets bud where'er we turn our mazed eyes.

The poet is apparently chasing images he has difficulty to catch, that he cannot yet arrange in a pattern through which all and each of them may be justified. A thin, tremulous film enfolds the mermaids like a vest: as it flutters in the breeze, effects of changing hues are produced:

... And was as tho' some sapphire molten-blue

Were vein'd and streak'd with dusk-deep lazuli,

Or tender pinks with bloody Tyrian dye.

This simile is more reminiscent of Wilde at his worse than of anything one would connect with Hopkins himself: think of poems like `The New Helen' or `The Sphynx', for example:

Hast thou forgotten that impassioned boy,

His purple galley and his Tyrian men

And treacherous Aphrodite's mocking eyes?

("The New Helen")

Incidentally, in the same poem, just a few lines ahead `gold-crested Hector' is recalled: is it just by chance, I wonder, that the thin veil of the mermaids is also compared to Hector's casque when it is seen drooping over the mermaids' brows? The mermaids then crowd to the rock, where the beholder is sitting, like apple bloom blown up in the air by the winds of approaching summer. The description of the swirling bloom is joyful and rich in detail, but its effect is weakened by the lengthy simile, which is based on classical Greek models, whose sense of necessity and immediacy, however, it does not possess, and rightly so, for while simile was in the first place an instrument of knowledge for the ancient Greeks, for Hopkins at this stage it is but an imitation of the classics, a device he has borrowed from literary tradition. Another screen which blurs the directness of imagery is the personification of summer and spring. It is clearly just a trick: gods were living, sublime, disquieting presences for the Greeks: they were felt as a medium between man and the mystery of the world, but for young Hopkins they are no more than crutches on which to rest weak wings not yet ready for flight.

In one of the many fragments of `Richard', a poem Hopkins was never able to conclude, metaphor and simile occur after each other with interesting effects, which, however, are given no chance of development:

He rested on the forehead of the dawn

Shaping his outlines on a field of cloud.

His sheep seem'd to step from it, past the crown

Of the hill grazing:

The metaphor, based as it is on a complete identification of the observer and the observed, is a good one; on the other hand, the simile, not a conventional simile of the kind `X is like Y', but rather built on a construction which expresses or implies similitude , disturbs the free flowing of the image in its attempt to give unneeded explanations: the reader is immediately aware of it and Hopkins himself probably had the same feeling: the result shows there was a quick fall of motivation, after which no further creativity could be possible. The `drowsy numbness' which made Keats' senses still more alert to the song of a nightingale, is diluted into a descriptive mood, which calls to mind `The Lady of Shallott' rather than `The Ode to a Nightingale', so that here Hopkins sounds like a minor Tennyson rather than a minor Keats.

Another fragment showing how simile was probably just a device to convey still more accurate descriptions of nature for young Hopkins, a repository of analogies and details for some yet dim subject or emotion to come, is `All as that moth', probably dating to 1864, when Hopkins was just twenty years old:

All as that moth call'd Underwing, alighted,

Pacing and turning, so by slips discloses

Her sober simple coverlid underplighted

To colour as smooth and fresh as cheeks of roses,

Even so my thought the rose and grey disposes.

In the same way, `Like shuttles fleet the clouds', still another fragment, perhaps intended to be part of `Floris in Italy', looks more like a quick note with a rhythm than a real quatrain from a longer poem. It witnesses of the functioning of Hopkins' mind, particularly in those years, the early sixties: a mind eager to catch the fleeting moment and to record it as quickly as possible for fear it might disappear for ever, as I am like a slip of comet,

Scarce worth discovery, in some corner seen

Bridging tis evidenced also in his diaries. Another interesting case is `I am like a slip of comet', a short fragment of 1864:

he slender difference of two stars,

Come out of space, or suddenly engender'd

By heady elements, for no man knows:

But when she sights the sun she grows and sizes

And spins her skirts out, while her central star

Shakes its cocooning mists; and so she comes

To fields of light; millions of travelling rays

Pierce her; she hangs upon the flame-cased sun,

And sucks the light as full as Gideon's fleece:

But then her tether calls her; she falls off,

And as she dwindles shreds her smock of gold

Amidst the sistering planets, till she comes

To single Saturn, last and solitary;

And then goes out into the cavernous dark.

So I go out: my little sweet is done:

I have drawn heat from this contagious sun:

To not ungentle death now forth I run.

Once the simile between the self and the comet has been set up, Hopkins proceeds to describe the comet as it grows bigger and brighter the closer it comes to the sun. The description is accurate, meticulous; the celestial body emerging from the unfathomed depths of the universe, first scarcely visible, then more lively and cheerful as it spots the sun, is intensely contemplated. Then the eye follows the dying out of the comet as it moves away from the sun, till she comes / To single Saturn, last and solitary; / (an image, this, which is well worth Milton) And then goes out into the cavernous dark.

At this point, in the last three lines, the poet goes back to the first term of the simile - the contemplating self - to stress its analogy with the comet; like the star, the self has been inflamed by a Contact with God, this contagious sun, and has been changed by it. After the moment of vision, the self is dimmed again, but once God has shown his face, life will never be the same, and not an ungentle experience. It is the first step towards the long ascent of Mount Carmel, which will finally lead to the mystical vision. Before this is possible, the soul will have to cross a dark night of discomfort, just like that comet making its way through a dark universe before it receives full light by a burning sun.

However, what is left in the reader's mind when the poem is over is not the memory of an analogy: rather, it is the image of a comet sweeping the sky, brightening it a little while and then disappearing into the unknown. The reason is simple: the simile has been set up to clarify some point, but then the poet has been immediately caught by the wonder arising from the contemplation of a natural phenomenon, which is what really matters for creative imagination.

Still in other words: the moral or spiritual dilemma which has given rise to the simile is not yet central in the young poet's mind; as a consequence, the simile is not really concerned with solving this dilemma. At this point, the only real use of the simile has been to introduce the powerful image of a moving celestial body, and the excitement that image has aroused has been enough to remove the main reason why it had been introduced. As a consequence, when the simile comes back at the end of the poem, its logical implications have become irrelevant and are quickly forgotten by the reader. But in 1866 G.M. Hopkins, then a young man of twenty two, came out with an utterly different poem, Nondum, in which the use of simile changes dramatically. There are just three similes, but they are placed at as many pivotal points, which give the poem its special colouring:

We see the glories of the earth

But not the hand that wrought them all:

Night to a myriad worlds gives birth,

Yet like a lighted empty hall

Where stands no host at door or hearth

Vacant creation's lamps appal.

. . .

And still th'unbroken silence broods

While ages and while aeons run,

As erst upon chaotic floods

The Spirit hovered ere the sun

Had called the seasons' changeful moods

And life's first germs from death had won.

And still th'abysses infinite

Surround the peak from which we gaze.

Deep calls to deep, and blackest night

Giddies the soul with blinding daze

That dares to cast its searching sight

On being's dread and vacant maze.

. . .

Speak! whisper to my watching heart

One word - as when a mother speaks

Soft, when she sees her infant start,

Till dimpled joy steals o'er its cheeks.

then, to behold Thee as Thou art,

I'll wait till morn eternal breaks.

It is interesting to notice that, unless you learn all the lines by heart, what will hold in your mind is two main images: one, that of an immense solitude all surrounded by an appalling silence; the other, that of a lighted interior in which absolute silence is finally broken by the familiar sound of a mother's voice. Nondum is really a meditation on the silence of God, an anticipation of the dark night of the soul that every mystic must expect to face, a terrible experience, which will cause `cries countless' in Hopkins' late poetry. The silence filling the poem is that of the infinite space immersed in a primeval night or coldly lighted by lifeless suns. The two images - that of the external space and that of an interior - are firstly balanced by the usual connectors of traditional simile - `like', `as' - but the two terms soon some together and merge into each other, like two ice cubes left too close to each other. The final impression is that one cannot draw the line between the scaring silence of the cosmos and that of the empty hall. Adjectives, nouns, verbs in the other stanzas can be applied to both. Similarly, in the last stanza, the soft voice of a mother speaking to her infant is able to bring back calm, peace and order both into the small bedroom - which is also the lighted empty hall of another stanza - and to the abysses infinite of a universe, till then frightening and unintelligible'. Contrary to certain metaphors, which still bear the mark of the similes they come from, these similes are already ripe with the metaphors they are struggling to become.

The impact they have on the reader is the opposite of that which proceeds from a worn out or trite metaphor: while the latter makes one think of some unwinding mechanism, the type of simile I am discussing seems to be charged with a visionary force capable of combining together two different levels of reality to produce a q emotional response, not unlike that brought about by a creative metaphor.

The cognitive process which underlies the production of a metaphor is probably the same as that which is triggered by a simile, with the obvious difference that a simile is mostly more explicit in its attempt to compare what is not yet clear in one's mind with what has already been acquired through education and experience. It is true that, as Paul Kiparsky puts it, metaphor is frequently linked with a certain type of semantic deviance;. `However, - he adds - it is clear that nondeviant sentences can have metaphorical interpretations: take, for example, He came out smelling like a rose. In fact, the processes by which we give metaphorical interpretations to deviant sentences are the same as those by which we understand latent meaning in nondeviant sentences' .

What does this imply? That apparently the borders between simile and metaphor are not so clear cut as Boyle would put it. Some similes are open to what Kiparsky calls metaphorical interpretations. In other words, it is impossible for a linguistic structure which usually introduces a simile not to urge a rhetorical response leading to logical statements. As an instance, if I follow the flight of a bird in the sky, the concentrated effort of all my senses can be expressed verbally either by a metaphor or a simile.

The final choice will depend not so much on the quality of observation, but on my psychological and moral disposition during the experience and when I finally decide to write a poem on that experience. If, for example, I follow that flight with the feeling that it is the image, a symbol, of some other event that I cannot circumscribe or define, my need to communicate this emotion will probably require a metaphor. Describing that flight will bring about not only an aesthetic pleasure, but also a moral and spiritual emotion which will be almost impossible to keep separate from it.

The reader of the poem will perceive this close connection between aesthetic pleasure and moral vibrations when the image is the result of this complex perception of reality. The flight of the bird could also be described by drawing more explicit analogies with other aspects of experience: in this case, a simile rather than a metaphor will probably be used, and the reader's response will have to be different: more detached, maybe, with a higher degree of intellectual rather than emotional enjoyment.

The Mature Poet

But there are similes of a very different kind, in which the rational process of comparison and the clear-cut distinction between the two terms of the comparison fade into a sort of no man's land in which the features of the two levels of thought, existence or development being compared merge into each other producing an emotional response which is not too far from that which we expect from a good metaphor. This may happen when the tertium comparationis becomes the focus of poetic imagination; in other words, when the poet chooses to concentrate particularly or entirely on the quality or qualities the two terms have in common, and, by doing this, loses sight of, or amalgamates into one experience, the individual aspects of the terms which initiated the process of comparison itself, so that the reader can no longer make out which is which, because that is no longer clear to the poet himself.

In the case of Gerard Manley Hopkins, it is this mechanism which is likely to stay behind the subtle, at times imperceptible, passage from a simile to a metaphor, especially in his mature poems, or behind the incorporation of a metaphor in a simile. For instance, both A Vision of the Mermaids and The Starlight Night provide the reader (or listener) with images of flowers in bloom; in both, the image is part of a simile; however, the impression one receives is quite different in the two poems. In the first poem it is as if we were invited to follow the description of a beautiful spot swarming with a rosy cloud of petals, then to concentrate on the mermaids crowding on a rock so that we can see the analogy. In The Starlight Night, written some fifteen years later, the stars are compared with the rich mess of an orchard bough and then with sallows in bloom; but, before that, the stars themselves have become metaphorically a May-mess and March-bloom, so that the simile is not between two objects or phenomena, but between a metaphorical image and a realistic image. Add to this that you are given two similes in two lines with the result that they merge in our minds to give us not two images, but one complex image in which the March-bloom is not only connected with the mealed-with-yellow sallows, but with the orchard-boughs, which do not appear as laden with fruit, but rather swarming with blossom. The result is not just a description, but an emotion which adds to and completes the one called forth and provoked by the first exclamation which opens the poem: Look at the stars! look, look up at the skies!

Another famous poem, The Caged Skylark, is based on a similitude between a caged skylark and the spirit of a man, a prisoner of flesh. An analysis of this short poem could start from this structural peculiarity, which it has in common with a small section of Il Mystico, where the description of a skylark also occurs. Here the state of bliss of the mystic is compared with that of a skylark in flight and to its joyous singing. If we compare the different impact the two poems have on us, the readers, we shall see that in The Caged Skylark, as in The Starlight Night, the simile sets in motion a mechanism of full identification of the two terms of comparison, which are then perceived as a unity, as in a metaphor; in the earlier poems all this is not discernible, and we have a feeling of coldness and indifference, or wander freely from one image to another, some of them even beautiful, but not qly connected to one focus.

Once the simile-generating process is set in motion, it may lead far from the initial effort to catch similarities or dissimilarities between two terms in comparison. Fancy may grow into imagination and the peculiarities of the object or phenomenon under scrutiny may be forgotten and transcended in an experience of wholeness. The similes Hopkins devises in some of his major poems do reach these levels of sublimation: one of the two terms of comparison often incorporates or is itself a metaphor: the emotional response it calls for affects also the second term of comparison, so that the distinctive features of the latter are soon forgotten. The similes in poems like Hurraying in Harvest; The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air We Breathe and God's Grandeur could be all read under this light.

Conclusion

In his early production and when he is scarcely creative, Hopkins uses similes as a tool to explore the world and to compare it to that other world, his inner self, which is unknown and fascinating; but later in his life, and poetic career, and when he is most creative, simile is often strictly interwoven with metaphor and quite indistinguishable from it, at least for the effects it produces on the reader. The function of such a kind of simile is no longer that of scanning reality so as to have a closer and more analytical view of it; rather, it helps bring together different levels of reality - physical and moral, natural and psychological - by concentrating, not on the two terms of a comparison, but on the tertium comparationis, that great magmatic repository of feelings, notions, images, recollections from which Hopkins, like an ancient god, moulds living beings - his powerful images - by blowing into it the creative and redeeming breath of poetry.

Notes

- Metaphor in Hopkins, R. BOYLE, SJ, Chapel Hill, N.Car: 1961, p. 175.

- ibid.

- I follow Coleridge's interpretation of the two terms as discussed in his Biographia Literaria.R. BOYLE, p.182.ibid. p.178.SERPILLO, G, `Moulding this Brute, Restraining Matter: Hopkins, His Translators and temporary Truth', in Gerard Manley Hopkins Annual 1992, edited with an Introduction by Michael Sundermeier, Omaha, Nebraska: Creighton University Press, 1992, pp. 37 — 57.

LAUSBER, H,

Elemente der literarischen Rhetorik, 1949 (Italian translation, Elementi di retorica, Bologna, 1969).LEECH, G.N. and M.H. SHORT

, Style in Fiction: A Linguistic Introduction to English Fictional Prose, 4th impr 1981; rpt. London and New York: Longman, 1984, p. 88.- ibid.

KIPARSKY, Paul,

The Role of Linguistics in a Theory of Poetry, in Essays in Modern Stylistics, ed. D.C. Freeman, London and New York: Methuen, 1981, p. 17.

Of course it would still be possible for a reader to see analogies where the poet had none in mind. All poets have had this curious experience: to realize how their readers were so good as to find hidden meanings, complicated analogies and symbolic implications where their own approach had been direct and quite innocent. this is perfectly sensible: any reader has a right to look for something, in a poem, which will foster his quest for a moral purpose or for a symbolical interpretation of life; however, if you read the poem with some detachment and with the appropriate critical instruments, it will be the inner articulation of the poem itself (the relationship between its title and its contents, for example, isotopes, explicit or implicit cross reference) and its relationship with the macro-text that will bring back the piece to its original purpose, the way a painting can be restored to its former beauty after centuries of mishandling have burdened it with useless and ugly encrustation.

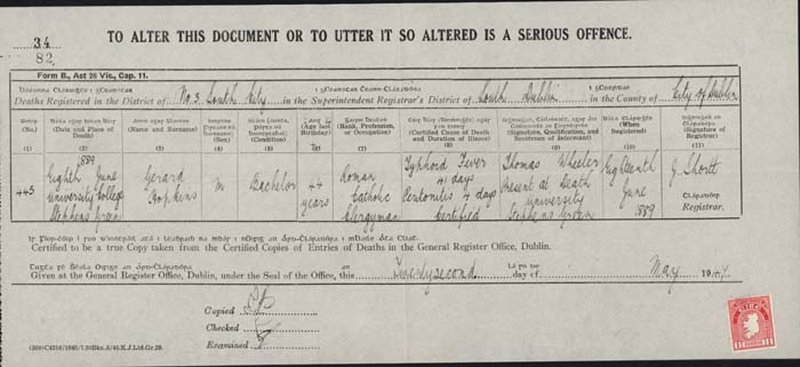

- Gerard Manley Hopkins applies for a teaching position in the Royal University Dublin - autograph copy of letter

- Hopkins Dies in Dublin and is buried in Glasnevin Cemetry. Patrick Lonergan gives an account of Hopkins's death and funeral

- Gerard Manley Hopkins in Dublin (2012): Michael McGinley

- Hiberno English and Gerard Manley Hopkins's Poetry (2012) : Desmond Egan

Lectures delivered at the Hopkins Literary Festival since 1987

© 2023 A Not for Profit Limited Company reg. no. 268039