Hopkins Poetry: Inscaping the Heart

Aleksandra Kedzierska,Instytut Anglistyki,

UMCS,

Lublin,

Poland

Inscaping the heart, a recurring theme in the poetry of Hopkins,concerns itself with beauty, directs the reader heavenward. Inscape marked each stage of Hopkins's spiritual and poetic progression.

Inscaping the heart, a recurring theme in the poetry of Hopkins. The heart concerns itself with beauty, directs the reader heavenward. Its presence marked each stage of Hopkins's spiritual and poetic progression. The heart tells its tale of love. This essay, by Aleksandra Kedzierska

, discusses heart imagery in the poetry of GM Hopkins.

In one of his juvenile pieces, Hopkins has his persona, Floris in Italy, express this wish: And I must have the centre in my heart/ To spread the compass on the all starr'd sky.(Floris in Italy) Almost like a motto to Hopkins's later works, these words point to the prominence of the heart which, ready as it is to concern itself with beauty, directs the reader heavenward. Recurring from poem to poem, its presence marked in each consecutive stage of Hopkins's spiritual and poetic progression, the heart seems to be telling its tale of love: the story of the man who after years of groping in the vacant maze of the Anglican Church, found, in Catholicism, the Real Presence of Christ to whom he dedicated his life and the fragile words of his poetry. In its attempt at reconstructing his story, this essay will discuss various representations of the `heart' image as they reveal themselves chronologically in Hopkins's poems.

As if "victimized" for his anthropocentric perception of the world, doomed to remain forever incomplete, Floris is by no means the only loser among the protagonists of Hopkins's preconversion works. Another man determined to measure his universe outwards from my breast must eventually find that despite his explorations the earth and heaven are still only so little known to him (The earth and heaven so little known). A grief-stricken lover in A Voice from the World comes to recognize the hardness also of his own heart -- "this ice, this lead, this steel, this stone. Only when rejected, does he begin to analyze his relationship with the Divine, determined, for the sake of his beloved, now heavenly far, to [m]ake it to God, hoping that one day his passion-pastured thought may indeed turn to gentle manna and simple bread. His hope for salvation seems justified in view of the words Christ Himself directs to a far greater sinner, Pontius Pilate: If you have warmth at heart, this shall need no further art. (Pilate)

In The Beginning of the End (1865), where the poor love's failure finds another vignette, the image of the bankrupt heart serves to convey the poet's awareness of the imminent collapse of his old Oxford world. Having no more tears to spend; losing heavily, the only goods the heart seems to capitalize upon are shame, disillusionment, and bitterness. Although the despicable cries; storms and scenes are not the symptoms of the crush'd heart referred to in But what indeed is asked of me? (1865), the speaker's mental strain and confusion linger on, pointing, this time, to the real source of his distress. Far more serious than a lover's neglect is the uneasy silence of the Divine, which, strengthening Hopkins's alienation, makes him feel disparadized.

The failure of the heart, which, despite its hunger for Love and its efforts to find a way to heaven, cannot be buoyed above is also registered in My prayers must meet a brazen heaven (1865).

My prayers must meet a brazen heaven

And fail and scatter all away.

Unclean and seeming unforgiven

My prayers I scarcely call to pray.

I cannot buoy my heart above;

Above I cannot entrance win.

I reckon precedents of love,

But feel the long success of sin.

My heaven is brass and iron is my earth:

Yea iron is mingled with my clay,

So hardened is it in this dearth

Which praying fails to do away.

Nor tears, nor tears this clay uncouth

Could mould, if ant tears there were.

A warfare of my lips in truth,

Battling with God, is now my prayer.(27)

Praying, the heart projects a vision of God as a severe judge, as distant and unresponsive as the brazen heaven He inhabits. Chaining the man stronger to his sins rather than helping him to open up to God's closeness, it steers him towards the imminent desolation. Consequently, incapable of any deeper involvement that could result in its own flight towards God, the only kind of experience this hardened, earth-enslaved, heart seems to know is a warfare of words which, hurled at God, are like "dead letters" that never elicit the desired response.

However, with time, the watching heart learns its lesson and manages a prayer which, in view of its straightforward and direct address, and as Nondum (1866) indicates, may be hoped to negotiate the heavenly heights. Addressing the reverently capitalized Thee of the poem, the trembling sinner, caught between faith and unbelief, wavers articulating his uncertainty concerning God's presence in the world and his dire need to feel it. Here, facing the truth of his heart's desire, he pleads that the God he so desperately hungers for is not like a Victorian tyrant-father, but like a joy-giving mother, always ready to tenderly embrace her child and mantle him with her love.

Oh! till Thou givest that sense beyond

To shew Thee that Thou art, and near,

Let patience with her chastening wand

Dispel the doubts and dry the tear;

And lead me, child-like by the hand

If still in darkness not in fear.

Speak! whisper to my watching heart

One word - as when a mother speaks

Soft, when she sees her infant start,

Till dimpled joy steals ov'r its cheeks.

Then, to behold thee as Thou art,

I'll wait till morn eternal breaks.

Sadly, even this heart so alert to the traps of sin seems to experience God mainly as fear, perceiving Him, at best, only in terms of either... or, and hence proving itself beyond the grasp of the paradox of winter and warm, beyond the mystery of the dark descending, most merciful when darkest.

When finally experienced in The Wreck, this initiation into the horror of grace enables the man to acquire the heart right, metamorphosed in the process of divine refashioning into that unique compass Christ is, the only landmark, seamark, the soul's star. Like the poet whose conversion story it renders, wrung by the Father and fondler of heart, the heart is swept, hurled, trodden down, laced with the fire of stress, and almost unmade, till instressed, tuned afresh to God's touch it proves capable of kissing the rod. Energized by the Real Presence of Christ which it could eventually experience, the heart celebrates its rebirth with the fiat fling till finally anchored in the heart of the Host, flushed by grace and united with All-in-All, it melts into completeness.

I whirled out wings that spell

And fled with a fling of the heart to the heart of the Host.

My heart, but you were dovewinged, I can tell,

Carrier witted, I am bold to boast,

To flash from the flame to the flame then, tower from the grace

to the grace. (iii) p. 52)

Thus, from a preconversion bower of grief, the heart - which after all is Hopkins's favourite image ( only in The Wreck it is evoked 18 times), becomes a territory where, to quote E. Borkowska, unity renders itself present...the place where God dwells and man flings to...to be delivered and rescued... the tabernacle in which the poet-priest has access to during daily liturgy (77). Enhancing the dialogic (cf. Badin, 65) as well as dramatic structure of Hopkins's poems, the convert's heart performs its many roles: of the protagonist on the making, of the addressee of the speaker's words, and/or of the altar on which the Eucharist is received and the trials of Calvary re-enacted. Besides, this powerful instrument of cognition becomes the only source of knowledge of mystery of God's stress (cf. Cotter Inscape,151) and a witness of the miracle of the manger: of Christ reborn, and physically brought into the human world by the call of the shipwrecked nun.

What is more, when, following the example of his sister in faith, he too, tries to utter the holy name, his heart throes translate into the complex definition of the Divine inscaped, stanza by stanza, throughout the ode, an externalized portrait of the most exquisite mother of being, the all-embracing Omega - the heart of all Love and creation.Nourished by and growing in the Real Presence of Christ, enlightened by heart-to-heart communication -- the spiritual fulfillment of the love between man and God, Hopkins found strength to recreate the communion experience in The Windhover and Hurrahing in Harvest ( titled in one of its early versions as Heart's Hurrahing in Harvest; cf. Delli-Carpini, 99), two nature sonnets written shortly before his ordination (1877). In The Windhover, caught by the speaker, Christ responds by touching the human heart, and leaving His instress there makes it the achieve of, the mastery of the thing! Though at first at hiding, the speaker's heart nevertheless stirr[s] for a bird to finally plunge into a revelatory prayer of adoration :O my chevalier!; ah, my dear. Having recognized its Master in the sign of the falcon, the heart sees through the brute beauty of the bird, sensing the power and beauty a billion times lovelier and more dangerous, against which it can only buckle in the humble fiat of submission. This moment of homage allows the heart to accept the sheer, unspectacular drudgery of existence with all its bruises, the blue-bleak embers; gall; and gash, and thus to embrace the darker side of faith, which, somehow does not mar the happiness of the encounter. In Hurrahing in Harvest, a poem as ecstatic as its title, lifted up to the sky, the heart gleans our Saviour and glories in the [r]apturous love's greeting which, once experienced, must be responded to in reeler... rounder replies. All of a sudden earth and heaven, both full of Christ, become one, the world of love in which an almost mystical union of man and God becomes possible.

And the azurous hung hills are his world-wielding shoulder

Majestic - as a stallion stalwart, but very-violet-sweet!-

These things, these things were here but the beholder

Wanting; which two when they once meet,

The heart rears wings bold and bolder

And hurls for him, O half hurls for him off under his feet. (70)

The Lord-loving heart dances another fling, revealing itself as the beholder wanting, ready to throw itself into this rendezvous with God and to open up to the surrounding paradise, experienced not just spiritually, but as a concrete, physical presence. To the heart capable of reading the book of God's creation, Christ's world-wielding shoulder becomes perfectly visible. Instressed in things big and small, in the hills and in a tiny violet, powerful yet at the same time subtle and tender, Christ appears as a perfect Lover, unmatchable in the generosity with which He pays for the slightest indication of human affection and concern. His rewards for the exultant heart are many indeed. Initiated into the mystery of the world, tangibly demonstrated in its sanctity, the heart obtains its greatest prize -- Love itself, and through this also freedom, allowing the poet to experience the elation of flight. Finding in Christ both courage and strength to hurl itself, capable, if only for a short moment, of forgetting the heaviness of the uncouth clay, the heart rears wings bold and bolder, and, bird-like, offers to God the prayer of its flight. After his ordination, the works of Father Hopkins began to reflect a change of heart, this image being employed first and foremost to render the wide-ranging gamut of responses to God that the priest-poet observed among those for whom he cared. He would warn that without Earth's...heart -- the dear and dogged man, everything would be given over to rack and wrong

(Ribblesdale, 1882).

In Caradoc, he portrayed the man who, loyal only to his own soul, has lost track of his heart, turning thus into the image of perfect pride (St. Winefred's Well). He spoke of the hardened hearts of oak (The Loss of the Eurydice, 1878), criticizing also man's neglect of the vital candle of God's light, (The Candle Indoors, 1879), or excessive concentration on heart's cares in The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo (1882).Teaching through positive examples, he would mention the heart fine of a cheery beggar (A Cheery Beggar, 1879), better still, the heavenlier heart Felix Randall (Felix Randall, 1880), a furrier developed when anointed and all or else the mannerly heart of a sacristy helper, a treasure exquisite enough to merit a special meditation on its handsomeness.

But tell me, child, your choice; what shall I buy

You?"

father, what you buy me I like best.'

With the sweetest air that said, still plied and pressed,

He swung to his first poised purport of reply.

What the heart is! which, like carriers, let fly—

Doff darkness, homing nature knows the rest-

To its own fine function, wild and self—instressed,

Falls light as ten years long taught how to and why.

Mannerly—hearted! More than handsome face —

Beauty's bearing or muse of mounting vein,

All, in this case, bathed in high hallowing grace

Of heaven what boon to buy you, boy, or gain

Not granted Onl O on that path you pace

Run all your race, O brace sterner that strain! (8182)

Hopkins's parish duties did not prevent him from tending his own heart. Looking into it, aware, as in Peace where he refused to play hypocrite / To own my heart, of its corrupting potential, he admonished himself to mend his own fading fire so that he could aggrandize and glorify God also in his inner sanctum (The Candle Indoors). Occasionally, allowing for a surge of emotion which, treasured, he stored in the heart's memory, he would mention how touched he was by the tears of a suffering man (Felix Randall) or how it did his heart good (The Bugler's First Communion, 1879) to work for the greater glory of God, administering the first communion to the boy bugler.

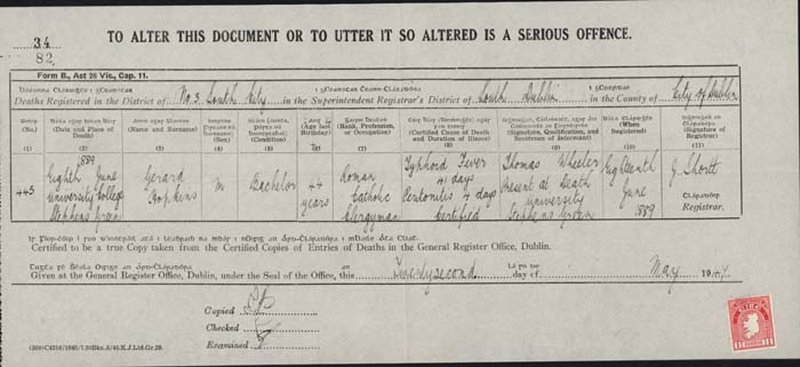

In 1884, in the lonely began of Dublin Hopkins underwent a spiritual crisis far more stormy and wrecking than the one he had experienced as an Oxford student. Recorded in the terrible sonnets, the rendering of the experience of the dark night of the soul owes some of its frightening power to the depiction of the heart. Being mastered again, tested in its acceptance of Thy terror, O Christ, O God, the heart finds itself enveloped by the darkness of confusion blurring the difference between heaven and hell. Although, as made clear in To seem the stranger (1885), it was viewed as the main source of wisdom and creativity, now all the heart's attempts miscarrry, stifled by hell's spell or baffled by the ominously dark heavens. Under the siege of such enemies the heart closes itself to them and in this remove of its own doing, deprived of any outside help, it must cope with its fears and resentment completely alone.

The torment intensifies in I wake and feel (1885), where, the dis-incarnate (cf. Harris, 55), despairing poet, enters into a relation with his own heart. On the one hand he perceives it as part of the space of the self into which he has plunged and through which he gropes. On the other hand, the heart appears to him a separate entity, a companion - perhaps the Sacred Heart of Jesus - (cf. Goggin

, 93) independent enough to explore the horrors of darkness going its own ways. Estranged from the self-torturing poet, though still retaining its role of an addressee, the heart becomes the witness of Hopkins's negative metamorphosis. Like a rebel, dogged in a den, having forgotten that every dark descending is of God's doing, the man, alienated from his heart, and therefore no longer truly human, can perceive and interpret reality only in a fragmented, defective way Burning with its gall, poisoned by the sin of pride, the heart becomes an impenetrable border which not only does not allow for any divine intervention, but also prevents Hopkins from meeting and communicating with his truest self.Patience, hard thing (1885) provides another insight into the man's natural heart which emerges as a peculiar cemetary of hopes, whose ruins are masked by Patience. Allied with the elective rather than affective will, the heart's very special inhabitant eventualy causes the war within which, fought between the man's instinctive and religious selves, brings about his spiritual maturity. The fight's painful intensity is effectively rendered by the sound of grating and it is to this accompaniment that the man's rebellious wills are bent, thus completing the process of reforging of the heart. Now the wisdom instilled through dear bruising will teach man to accept God on God's terms.Complete again, wiser for another toss he has taken, filled with patience and hope, the poet can finally instruct his heart:

My own heart let me more have pity on; let

Me live to my sad self hereafter kind,

Charitable, not live this tormented mind

With this tormented mind tormenting yet. (102)

Fire and of the comfort of the Resurrection (1888), a sonnet in which the heart's clarion triumphantly announces the end of its Dublin night:

Enough! the Resurrection,

A heart's clarion! Away grief's grasping, joyless days, dejection.

Across my foundering deck shone

A beacon, an eternal beam. Flesh fade, and mortal trash

Fall to the residuary worm; ...

In a flash, at a trumpet crash,

I am all at once what Christ is, since he was what I am, and

This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, patch, matchwood, immortal

diamond,

Is immortal diamond (107)

The joy of the heart as it is reached by an eternal beam and resurrected from grief allows it to realize the power of God's love for every Jack. Although a mere potsherd, a sinner on his foundering deck, the heart has been approached and rescued by the Light. Enlightened and in a flash transformed into immortal diamond, liberated from the constraints of its cumbersome carnality, the heart rejoices in the oneness which it was created to become.As demonstrated above, skeined off the spools of desolation and happiness, of meetings and departures, the tale of the heart ends on an optimistic note. Written for over two decades, this tale embraces all the critical stages of Hopkins's spiritual development. It begins by first showing the frustrations of the heart forecasting about Rome which eventually led to the poet's conversion. It follows on to relate the transforming experience of the communion with the Divine, during which, dovewinged, the heart was made capable of flight and towered from the grace to the grace. Then, passing through the exaltations and frustrations of priesthood, growing older, grieving and strain[ing] beyond my ken, the heart plunges in its own darkness. Tasting its own gall and heartburn, it temporarily loses the sense of God's closeness till, relearning towards the end of the Dublin night the old art of acceptance and humility, the heart regains its power to lap strength. Shy at first, and only stealing joy, it can again laugh and cheer till its time comes to be claimed by the Saviour. Rescued from the foundering deck of self-doubt, exposed to the Light once more, it hears the clarion music of the Resurrection, and finds in this selfyeast the placidity Hopkins himself must have felt on his deathbed, when heard repeating I am so happy, I am so happy (Martin

, 413).

Notes

- Badin, Donatella. (1992) The Dialogic Structure of Hopkins's Poetry, The Authentic Cadence. Centennial Essays on Gerard Manley Hopkins. Fribourg: Fribourg University Press.

- >Borkowska, Ewa. (1992) Philosophy and Rhetoric. A Phenomenological Study of Gerard Manley Hopkins's Poetry. Katowice: Uniwersytet Slaski. Cotter, James Finn. (1986) Apocalyptic Imagery in Hopkins'`That Nature' Victorian Poetry. 24 (1986) 261-73. Inscape. (1972)

- The Christology and Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins. London : University of Pittsburg Press.Delli-Carpini, J. (1998) Prayer and Piety in the Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins: The Landscape of A Soul.

- Lewiston: Edwin Meller PressGardner, William H. - Norman H.MacKenzie (eds) (1970) The Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins. (4th edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press. All quotations from Hopkins's works come from this edition. Page number given in parenthesis.

- Goggin, E.W., (1989) The Terror Night: A Reading of `I wake and feel' The Hopkins Quarterly. 16 (3), pp. 89-100.

- MacKenzie, Norman H. (1981) A Reader's Guide to Gerard Manley Hopkins. London : Thames and Hudson.

- Martin, Bernard ( 1991) Gerard Manley Hopkins : A Very Private Life. London: Harper and Collins Publishers.

- Watson, J.R. (1989) The Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2001

- Search the Gerard Manley Hopkins Archive

- Albert Sweitzer and Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Thomas Hardy and poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Walt Whitman and Hopkins

- Christina Rossetti

- Albert Schweitzer and Hopkins

- Hopkins' Use of Imagery in his Porems

- Classical Chinese Poetry and in Hopkins' Poetry

- Inscape, Instress in Hopkins' Poetry

- Parmenides

- Thomas Hardy and Hopkins Poety

- What brought Whitman and Hopkins Close

- Overview Lectures 2001

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2022

- Landscape in Hopkins and Egan Poetry

- Walt Whitman and Hopkins Poetry

- Emily Dickenson and Hopkins Poetry

- Dualism in Hopkins