Gerard Manley Hopkins and Walt Whitman

… I always knew in my heart Walt Whitman’s mind to be more like my own than any other man’s living...

Desmond Egan Poet,Artistic Director,

The Gerard Manley Hopkins Festival

Newbridge

This Lecture was delivered at the Hopkins Festival July 2022

… I always knew in my heart Walt Whitman’s mind to be more like my own than any other man’s living. As he is a very great scoundrel this is not a pleasant confession. And this also makes me the more desirous to read him and the more determined that I will not. — so writes Hopkins in a letter to Bridges on 18 Oct. 1882 (C.C. Abbott, Letters p.155) in reply to a suggestion by Bridges that a chorus from Hopkins’s (unfinished) drama St Winefred’s Well (1879 - 1886) shows the influence of the American poet. In defence, Hopkins says that he had read only ‘half a dozen pieces at most’ of Whitman, plus a quotation in a review. Whitman had become enormously popular in England from the 1870’s on (Justin Kaplan, A Life New York, 1980 rep. 1982). The two poems mentioned by Hopkins (To the Man-of-War Bird - from ‘Seadrift’, and "Spirit That Form’d This Scene" - from ‘From Noon to Starry Night’, both 1881) were probably read by him in the early 80’s; the quotation mentioned came from a review of ‘Leaves of Grass’ by George Saintsbury in 1874.

Hopkins goes on to defend himself at length from Bridges’s suggestion of influence, Nevertheless I believe that you are quite mistaken about this piece and that on second thoughts you will find the fancied resemblance diminish and the imitation disappear. He says that, although both he and Whitman used ‘irregular rhythms’,

There the likeness ends. The pieces of his I read were mostly in an irregular rhythmic prose: that is what they are thought to be meant for and what they seemed to me to be. (Letter 18 Oct. 188,2 p.155).

‘Rhythmic prose’! Hopkins is energetically pointing out that his ‘sprung’ rhythm was very different from Whitman’s which, was ‘in its last ruggedness and decomposition into common prose’ (p. 157). Hopkins continues with what he later describes as a ‘de-Whitmaniser’ defence which would, he hopes, make Bridges change his mind about influence. He does, however, acknowledge Whitman’s marked and original manner and way of thought and, in particular his rhythm and allows that the few poems he had read might indeed be enough to influence his style, though he insists that such an influence has not taken place, For that piece of mine is very highly wrought. The long lines are not rhythm run to seed: everything is weighed and timed in them. Wait till they have taken hold of your ear and you will find it so.

All that said, Hopkins - in sending Bridges his Harry Ploughman poem five years later, (a year and a half before he died) asks, But when you read it let me know if there is anything like it in Walt Whitman, as perhaps there may be, and I should be sorry for that.” (Letters, Oct. 1887 p.262)

Why, then, might there be? Walt Whitman (1819 - 1892), his near-contemporary, was a great original and - consequently - enormously Influential poet. It was he who, more than any published writer of his time, broke away from the formal conventions of earlier poetry, introducing long, conversational lines dealing more directly with his own personality and world, and with the contemporary issues of America. In this, he is credited with having invented blank verse (soi disant) which has influenced most American poets from Pound and Eliot (mutatis mutandis) into our own time. His impact, then, may be compared to that of Hopkins, whose sprung rhythm introduced a new and therefore emotional freedom into poetry. (One of the things that amazes me is proof at the yearly Hopkins Festival of how widely Hopkins’s influence has spread across the globe. In the 50’s, for example, there was such a rash of Hopkins-influenced verse in Nigeria that one critic there railed against ‘the Hopkins disease’).

Whitman (1819—1892) was born in New York, worked at a printer’s; briefly became a teacher but spent much of his life as a newspaperman. often editing and writing as a freelance journalist. He printed and, published most of his own work either separately or in conjunction with someone, Along the way, he began (in 1855) his epic, autobiographical poem, Leaves of Grass, which he continued to add-to throughout his life and which finally ran to nine different editions, down to the year he died: a period of some 36 years. (Wordsworth’s autobiographical The Prelude continued from 1798 to his death in 1850: 52 years). Whitman also published six other Collections and a prose Autobiography. During the American Civil War, he worked as a voluntary male nurse in army hospitals, showing himself to be a compassionate person, with a great love for ordinary people, as against writers and artists, whose company he generally avoided.

Leaves of Grass (1855 to 1892) was revolutionary both in form and in content. In form, because it avoided earlier poetic structures in favour of long, rolling, almost prosaic lines — he said that his method of construction ’is strictly the method of Italian opera’ (which he loved) . So: passages of recitative rising on occasion towards lyric inspiration. Innovative, secondly, in content, because it is written in a directly autographical, almost extrovert, way. Critic Stephen Railton points out, (Walt Whitman, ed. Ezra Greenspan, Cambridge 1995 p.7) that there are few pages of Leaves of Grass which lack the personal pronoun (I, me, mine, my, myself) in some shape or form,

I know perfectly well my own egotism,

And know my omnivorous words, and cannot say any less,

And would fetch you whoever you are, flush with myself.

Another Whitman scholar, David S. Reynolds, (The Cambridge Companion to Whitman, C.U.P. 1995) describes his style as having, its air of defiance, its radical egalitarianism, its unabashed individualism, its almost jingoistic Americanism (p.66) and describes Whitman as exhibiting, The most confidently assertive poetic persona in literature (p.82)

Sadakichi Hartmann, in his short memoir (University Press Honolulu, 1894; rep. 2004) quotes Whitman’s own description as, the reflection of American life and ideas which reflect again (p. 10).

Not at all like Hopkins, then. They did have in common, though, a great love of nature which Whitman wrote about with an immediacy and freshness of response in ways comparable to that of the Jesuit poet. It is part of the American’s genuine, unforced sense of wonder at the beauty of all creation, male, female, the everyday, the ordinary… He admires anything natural. His sense of wonder would have gone down well with Hopkins:

Why, who makes much of a miracle?

As to me I know of nothing else but miracles,

Whether I walk the streets of Manhattan,

Or dart my sight over the roofs of houses towards the sky,

Or wade with naked feet along the beach just in the edge of the water,

Or stand under trees in the woods,

Or talk by day with anyone I love, or sleep in the bed at night with anyone I love,

Or sit at table at dinner with the rest,

Or look at strangers opposite me riding in the car,

Or watch honey-bees busy around the hive of a summer forenoon… etc. Miracles (‘Autumn Rivulets’ c.1881)

Like Hopkins, he responds intensely to the haecceitas, the materiality, of things: Hopkins for example to the ice patterns in an urinal; Whitman to the smell of an armpit or to the everyday grass:

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love, If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles. He respected religions and believed in a Creator, though he was not a member of any Church: .. I had perfect faith in all sects, and was not inclined to reject a single one. (Letter to Sarah Tynsdale, Life p. 231) It is not chaos or death — it is form, union, plan — it is eternal life — it is Happiness (Leaves Of Grass,1985 ed. p.88)

With his uninhibited directness, Whitman was not slow to celebrate the human body, especially the male, in terms which left little doubt about his own homosexual leaning - though he never explicitly came out. Nor did he, despite his bad reputation (which led to his poetry being banned in some States) descend into pornography, as some of his later followers - e.g. Allen Ginsberg - sometimes did. No other poet of Whitman’s time wrote about the body so joyfully and celebrated it so explicitly. The collection, ‘Calamus’, is rarely read as other than homoerotic, and Whitman is widely seen as a gay poet,

Without shame the man I like knows and avows the deliciousness of his sex, Without shame the woman I like knows and avows hers (l of g p. 111)

It is notable that, time and again - as here - when he seems to be speaking as a gay writer, he always qualifies his position to include female beauty as well. Some women writers of the time even considered him as what we might call a radical feminist. Interestingly, as Stephen Railton reminds us (op. cit. p.15),

It might seem hypocritical to argue that the least inhibited nineteenth-century American writer - the prophet of the body and its polymorphous pleasures - was seriously repressed himself, but I think that the testimony of Whitman’s whole life and work points to that conclusion. He could write much more evocatively, for example, about the beauty of the male physique than about the female, but could never bring himself to acknowledge that his attraction to men was sexual.

Reading Leaves of Grass, one is regularly aware of his refusal to make such an acknowledgment. It was the same in his dealings with various female admirers, notably with Anne Gilchrist, who came over from England to America in 1876 to marry him (Kaplan op.cit. p.366) - only to sail home disappointed three years later.

Over– all then, some comparisons with Hopkins can be made; and these may have contributed to Hopkins’s liking for Whitman — but the character differences are huge and there is little if any sign of influence in style.

Whitman differs, most immediately, in his brazen egoism - the very opposite to the humility of one who considered himself ‘time’s eunuch’. The American constantly writes - as we have seen - directly about himself. But it does not stop there. His self-absorption could lead him not only to promote his work shamelessly but even to publish reviews of it under an assumed name - as he did on a number of occasions. Much of his work was brought out by himself and he entered into the layout and sale of everything he wrote. (Interestingly, nearly every serious poet including Yeats, Kavanagh, Eliot, Pound, Kinsella… have self-published, faced with the indifference of the world to a poet’s calling.) His brashness offers a striking contrast to modest Hopkins. Whitman’s extrovert ebullience and in-your-face optimism seemed to tie-in with that of America itself, as it pushed forward energetically after the Civil War. His own rough and robust physicality can seem part of this energy and offers an immediate contrast with the sometimes melancholy, introverted, and often sickly figure of Hopkins,

Walt Whitman, a cosmos, of Manhattan the son, Turbulent, fleshy, sensual, eating, drinking and breeding, No sentimentalist, no stander above men and women or apart from them, No more modest than immodest.

(Song of Myself, no. 24)

The poetry is dynamic, full of unquenchable cheerfulness. His favoured words, Whitman himself suggested, were ‘robust, brawny, athletic, muscular…resistance, bracing, rude, rugged, rough, shaggy, bearded, arrogant, haughty’ (Daybooks and Notebooks p.738; quoted in Kaplan p. 229). His favourite pronoun is ‘I’.

Take, for example, his use of the present participle. Critic Ezra Greenspan (The Cambridge Companion to Whitman,1995, p.92 f.) has highlighted ‘participle-loving Whitman’ (in poet Randall Jarrell’s phrase) and what it implies,

Whitman had a lifelong attachment to the grammatical form of the present participle. It can be seen even in the titles of many of his

poems: I Hear America Singing, Starting from Paumanok, The Ship Starting, Going Somewhere, Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking, Crossing Brooklyn Ferry…there are 17 such titles in all, from every period. Many of his poems also open with participial phrases e.g. ’Sauntering… Facing… Chanting… Singing… e.g. in Song of Myself (no. 32),

Myself moving forward then and now and forever,

Gathering and showing more always and with velocity …

His liking for such modifiers of movement underlines his free-verse poetics and, as Greenspan points out, …his kinetic vision of … life as ceaseless, unauthorised … motion; of experience as an ongoing process…of his time and place as a fluid continuum transcending beginning and end points. (op.cit. p.96)

One is tempted to say, as a Heraclitean fire! Often, too, the act described in the poem is analogous to the act of the poet in making the poem’ (p.106) - though Greenspan, who never mentions Hopkins and his Windhover, prefers to find similar correspondences in Wallace Stevens.

Apart from Hopkins’s own sense of transience (which is movement) what words might typify his writing? Professor Suzanne Bailey in a fascinating lecture on ‘word clouds’ (delivered at the Hopkins Literary Festival of 2022) - a computerised examination of the prevalence of words in a poet’s work — suggests ‘heart’, ‘look’, ‘dark’, ‘lovely’, ‘hours’, ‘flame’,’father’, ’night’ among others - though her study of Hopkins from this perspective is not yet complete.

Hopkins may be just as ready to celebrate nature and the ordinary, as Whitman is - but with one crucial difference; one which highlights a major contrast between the two poets. For Hopkins, nature is almost always seen as a reflection of its Creator. His kestrel, so wonderfully realised, soon becomes a symbol of Christ. Hopkins’s celebration in Pied Beauty of, All things counter, original, spare, strange ends in an exhortation to ‘praise him’. And even when his sense of the mind’s ‘cliffs of fall’ is almost overwhelming, his poems never question his belief in a loving Creator: there is always some light even in his ‘dark’ sonnets. Whitman, we have seen, was a believer of sorts, Accepting the Gospels, accepting him that was crucified, knowing assuredly that he was divine. (Song of Myself no. 43) - but his belief tends more towards a pantheistic sense. Everything is miraculous, but the miracle lies completely in itself, All truths wait in all things … (Only what proves itself to every man and woman is so. Only what nobody denies is so.) (Song of Myself no. 30)

It is a peculiar belief: not atheistic, not agnostic, with something of the optimism of the transcendentalists of his time (Emerson; Thoreau). He was a Deist of sorts: believing in God but keeping him at a distance from human affairs. The poem Harry Ploughman does offer one interesting parallel to the Whitman approach. Unusually for Hopkins, it contains no direct religious reference. He points-out in a letter to Bridges (Nov. 7, 1887), that, I want Harry Ploughman to be a vivid figure before the mind’s eye; if he is not that (,) the sonnet fails. The difficulties are of syntax, no doubt.

In an earlier letter, written soon after his trip to Dromore Co. Down, where he wrote it, he describes the poem as, …a direct picture of a ploughman, without afterthought…let me know if there is anything like it in Walt Whitman (28 Sept. 1887)

The poem expresses a more straightforward celebration of natural handsomeness or beauty in itself than anything else Hopkins ever wrote: an attempt to describe the ploughman in his immediacy and glorious physicality. As such, it offers a challenge of his expertise to one of the great wordsmiths. Hopkins accordingly emphasises the technical virtuosity of his portrait, especially its rhythm, pointing out that it is ‘very highly studied’, in case Bridges might find it ‘intolerably violent and artificial’. (Letter CLIII/153), while making no comment about its content. As in The Windhover, the words are mimetic, taking-on something of the action, but this time no symbolism is suggested, no moral applied:

He leans to it, Harry bends, look. Back, elbow and liquid waist

In him all quail to the wallowing o’ the plough: 's cheek crimsons; curls ...

In making a comparison here to Whitman realism, we immediately face a fundamental difference of approach. While both poets are at pains about the run (rheo = to run) of a line, Hopkins’s sprung rhythm seems very different and much more subtle. Where Whitman generally settles for the freedom of a speaking voice; Hopkins aims to combine metrical freedom with control. His combination of counting the stresses in a line with a readiness to ‘spring’ across unaccented syllables, brings together a control - which is a sense of form - altogether more complicated and more expressive than Whitman’s hearty directness.The beat of a different drum. At root, Hopkins’s is a Christian perception. He believes in order. There is a fundamental contrast with the less complex irregular lines of Whitman, which at times can run very close to prose in their total rejection of metrical values.

Here we can identify a philosophical, even a metaphysical difference of standpoint between the two poets. This draws our attention to yet another contrast between the two poets: Hopkins’s overwhelming interest in words, in technique. But maestro though he is, Hopkins is no mere virtuoso: his experimentation is always a means, never an end in itself. He is no aesthete, no believer in art for art’s sake. Writing to Bridges almost a month after his defence of the difficulty of Harry Ploughman (Letters to Bridges, Abbott, Nov 6,1887) Hopkins makes an absolutely crucial observation - one establishing both his distance from the Whitman approach, and a defence against those who complain about the demands which his own poetry make upon us,

Epic and drama and ballad and many, most, things should be at once intelligible: but everything need not and cannot be. Plainly if it is possible to express a sub(t)le and recondite thought in a subtle and recondite way and with great felicity and perfection, in the end, something must be sacrificed, with so trying a task, in the process, and this may be the being at once, nay perhaps even the being without explanation at all, intelligible.

(op. cit. p. 265,6)

To the present writer, this is one of the most important statements re. the question of ‘difficulty’ in poetry generally. It is because of such ‘subtle and recondite thought’ (and the feeling behind it) that Hopkins as an exploiter of all the possibilities of language is unsurpassed. His sense of ‘inscape’, the inner core of things; his neologisms; his use of obsolete words; his compounding; his stretching of grammar; his Greek sense of etymology; his love of that Anglo Saxon power of language… all of these and more, allied to his peculiar and demanding rhythm - reflect the search of an extremely subtle mind and depth of feeling to express something complex, something beyond reach of prose explanation; where only poetry can go. Simply put: if you can ‘explain’ a poem fully, why was it written as a poem? Hopkins gives us the full resonance of a genuinely poetic vision. As he says apropos of the maidens’ chorus for his drama, St Winefride’s Well (which we know as ‘The Leaden Echo and The Golden Echo’) the poem was ‘very highly wrought’, but, the long lines are not rhythm run to seed: everything is weighed and timed in them

So why, finally, does Hopkins say that he always knew in his heart that Walt Whitman’s mind is ‘more like’ his own than that of any other man? (Note that he does not say ‘any other writer’). One answer might be the openness with which Whitman exposes his whole personality. (We may remind ourselves of Oscar Wilde’s being jailed for homosexuality in 1895; it only ceased to be a crime in England as recently as 1967).This might well have been a factor - though Hopkins did not show any liking for the poetry of other gay writers like Swinburne or the Oxford aesthetes led by John Addington Symonds and Lionel Johnson; and he never joined the ranks of the Decadents or Symbolists: Wilde, Ernest Dowson and company - though he had Walter Pater, their High Priest, as a Tutor in Oxford. He did not read much of Walt Whitman, and resolved not to. Let us not understand genius too quickly!

My own belief is that what Hopkins admires most in Whitman is what many poets, Pound and Eliot included, admired: the American’s ability to live in the absolute now, and in doing so, to celebrate the grandeur of existence in a way that shows a completely fresh openness to the possibilities of poetry, rejecting the tired conventions of past times. What matters most in Whitman’s poetry, what carries it and convinces us, is the flavour it always has of a full, vulnerable and compassionate personality. Such honesty is revolutionary. It brings a directness to his writing comparable to but distinct from Hopkins’s own astonishing freshness. Much of what passes for poetry, even when it gets beyond the manic rhyming stage, can offer mainly superficial emotion combined with an indifference to the resources of language, rhythm not least: in this area, many would-be writers seem caught up in the past. Not Whitman, though. Ezra Pound must have have been encouraged by this immediacy of response in his call to ‘make it new’. Thelonious Monk - another innovator in music - said that ‘a man’s a genius just for being himself’ i.e. wholly in his time and immersed in its rhythm; without jettisoning all past achievement. This is why Hopkins asks Bridges, in sending him a copy of Harry Ploughman, to let me know if there is anything like it in Walt Whitman, as perhaps there may be… (Michaelmas 1887 Letters p.262)

It is also why - in a subsequent letter - Hopkins is at pains to emphasise that this caudal, experimental, sonnet is nevertheless carefully constructed, while being ‘altogether for recital, not for perusal (as by nature verse should be)’. (Op. cit. p.263) He even daringly suggests that the ‘burden lines might be recited by a chorus’. So the poem is dramatic; immediate; challenging - qualities that also makes Hopkins an admirer of John Dryden, … above all this: he is the most masculine of our poets; his style and his rhythms lay the strongest stress in all our literature on the naked thew and sinew of the English language… (op. cit. Nov. 6, 1887, p. 267 f)

That is the kind of ‘thew and sinew’ which Hopkins admires in Whitman: words in use - rather than to be read; words, as he says to Dixon, of a ‘robustious sort’.

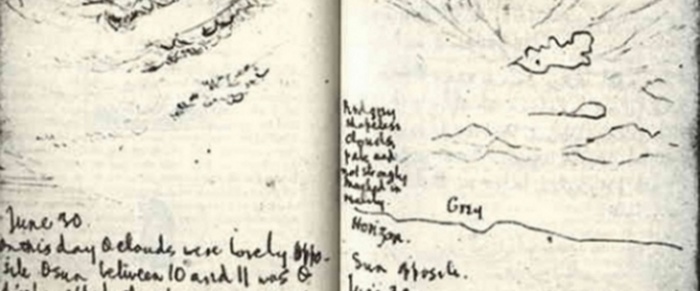

Turning to Harry Ploughman, one notices in the manuscript of the poem (manuscript A is chosen by Norman McKenzie, doyen of Hopkins scholars) the proliferation of diacritic marks. These are clearly intended to help in the recitation aloud, the performance, of the poem. As can be seen from Hopkins’s markings, suggests these include stress marks; pauses (‘a dwelling on a syllable’ independent of a metre); metrical stress wherever ‘doubtful’; circumflex marks ‘making one syllable really two’; circular marks running syllables together; a longer circle over three or more syllables giving them ‘the time of one half foot’; a circle underneath etc. for which he offers as explanation, … the outride under one or more syllables makes them extra metrical: a slight pause follows as if the voice were silently making its way back to the highroad of the verse

Norman Mackenzie quotes Hopkins as describing them (in manuscript A) as slack syllables surrounding the stressed, ‘outriders on the verge of the road’ (The Poetical Works, Oxford, 1992, p. 480). The ‘spring’ in sprung rhythm is from accent to accent; the unaccented ones, as in speech, play a secondary role - so that the rhythm undergoes another kind of springing, are freed (as in ‘sprung’ from jail).

Add to these considerations, the indented extras or ‘burden lines’ of this caudal sonnet - a fourteen-line Petrarchan sonnet but with an extra six lines or tail (‘cauda’) Inserted singly here and there. Hopkins indents these and even asks that ‘they might be recited by a chorus’.

It has been suggested that, because of all the quasi-musical marking on the manuscripts (of which three exist; not without wide discrepancies in the marking), Harry Ploughman is the most musical of all his poetry. I do not agree - nor does Hopkins, because he insists on its being ‘altogether for recital, not for perusal (as by nature verse should be)’ and again, he explains that these marks, are meant for, and cannot be properly taken in without, emphatic recitation; which nevertheless is not an easy performance. (letter to Dixon, 23 Dec. 1887)

Each poet wishes for a speaking voice, with its immediacy of tone and rhythm, in his poetry. In the case of Whitman, this could sometimes lead to his risking the casualness of statement, or of simple reportage,

From my last years, last thoughts I here bequeath,

Scatter’d and drop, in seeds, and wafted to the West,

Through moisture of Ohio, prairie soil of Illinois - through

Colorado,

California air,

For Time to germinate fully …

(My Last Years, (p.441) Is there much here that cannot be said in prose? That deepens into poetry? In his search for a direct voice, freed of the poetic forms, conventions, themes and oftentimes jargon of Victorian writing, Whitman takes risks which, though they revolutionised the assumptions of poetry, could themselves skate at times on the thin ice of banality. Hopkins on the other hand, though just as revolutionary, looks for an idiom which, though aiming at being spoken, also aims at an intensity of expression which combines the dramatic with the poetic. In ways, I believe, not dissimilar to T.S. Eliot’s search in his plays, for a poetic drama which manages to combine both of these strains. Eliot, while emphasising that ‘there is no freedom in art’ (Reflections on ‘Verse Libre’, 1917) and that, Vers libre (‘free verse’) does not exist… (a) preposterous fiction

He even goes so far as to say that he would consign such writing into ‘oblivion’! He draws attention to the crucial importance of achieving a rhythm in dramatic speech which ‘does not interrupt but intensifies the dramatic situation’ (Poetry and Drama, 1950). This involves what he had earlier described as the ‘auditory imagination’: What I call the ‘auditory imagination’ is the feeling for syllable and rhythm, penetrating far below the conscious levels of thought and feeling, invigorating every word; sinking to the most primitive and forgotten, returning to the origin and bringing something back, seeking the beginning and the end. (The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism, 1933) Such feeling for syllable and rhythm, indeed for language itself, ‘penetrating far below the conscious levels’ can carry us through many of Ezra Pound’s Cantos - as it can through some of Thomas Kinsella’s Peppercanister poems. I believe that where Eliot mostly failed (I mean in his Drama), and Whitman sometimes did, Hopkins succeeded, and at the most profound level, where technique and vision come together.