Landscape in Poetry of Desmond Egan and

GM Hopkins

Serpillo thought that Hopkins' and Egan's view of the landscape could be a useful starting point to appreciate the respective development of their poetry - perhaps acquire some new insight into their poetics.

This Lecture was delivered, July 2022, at the Hopkins Literary Festival

Giuseppe Serpillo

University of Sassari,

Sardinia.

Why compare two poets living two centuries apart, coming from different countries and cultural backgrounds? Hopkins spent the last five years of his life in Ireland and knew these surroundings quite well; he enjoyed the landscape of this country as much as he had loved that of England and Wales. Inspired by this fact, Desmond Egan created this international festival, being himself a passionate close reader and an expert of Hopkins.

I thought that their view of the landscape could be a useful starting point to better appreciate the respective development of their poetry, and perhaps acquire some new insight into their poetics. When we speak of the landscape we are referring to a complex experience in which all the senses are involved. Basically it is a synaesthetic experience: visual, olfactory, auditory and tactile perceptions affect the totality of the experience and are never the same for two or more individuals.

Besides,the same landscape is never objectively the same even for two different observers, and at the same time. The perceived is filtered through the individual psychology, sensitivity, and the anthropological culture of the perceptor. In short, the landscape, like any other experience, is all in the eye of the beholder, it is his/her own creation. I will consider four different types of response to the landscape: sensory, mythical, historical, ecological. The first is of course the most immediate: the landscape appears to the observer in all its variety, determining a response that is predominantly emotional, which could therefore be positive or negative but not indifferent; the mythical response implies that the landscape is seen as if animated from within by invisible presences referable to those that Jung assigns to the collective unconscious as moulded by the cultural context to which the observer belongs.

A different response is eliud if the landscape has been moulded by history; that is, when the observer sees in the signs engraved in that landscape the events that have altered/modified its contours or changed its substance; finally, the ecological response is that of those who, observing the landscape, notice the violence to which it has been subjected, feel indignation but also develop a sense of their own responsibility as individuals, as well as representatives of that society, which has disturbed its harmony. In Hopkins the landscape often does not arise from direct observation, but is pure creation of the imagination.

The landscape in Egan, instead, always arises from a direct, immediate or recollected experience, in one or more modes of perception. In Egan's poems, from 1975 to 1983, what prevails is a sensuality that feeds on sounds, images, shapes in motion. Absent h ere any reference to history or myth; the poet seems more interested in seizing that moment of life which immediately becomes a memory. This is evident for example in Glemcolmcille:

Glencolmcille

then we were standing on the top

the boggy surface yielding underfoot

there was cold from a salmon sea and mist

over the valley we were passing through our breaths hung too whisper it

making it somehow ours I thought

but it was hard to talk

hard to be consoled

better to find the track scramble down

before it got too dark

we still had to pitch a tent

somewhere

under the silent mountain ...

And in Clare: The Burren , the poet collects impressions, sensations dictated by a rough landscape, immersed in the fog. History does not emerge from those stones: it will do so later, in Peninsula. Here it is rather an emotional response to an object, the great dolmen — about which much has been read, studied — suddenly coming into view:

The red headed schoolboy (farmer’s son)

shyly led the way across

a livid wilderness of limestone striated with the ogham of ages

and there it stood

the great dolmen

In another poem of the same collection (Midland, 1972), Thucydides and Loch Owel , the Greek historian comes to mind for no reason , possibly an analogy between the beauty of the place and the harmony of Thucydides’ style:

Thucydides and Loch Owel

teal poised on ice

above the lake’s throb

this blue translucence

flexing across rocks

frozen sprays of fern

— Remind me of your History

for if the stretched town is become

part of nature so

are your sentences

like gulls they cry

down the cold shores

Even myth is only a memory of classical readings:

(memory’s Knossos the rustling labyrinths) as in the nebula of a dream

— Crete, Midland 1972

On the other hand, a strong feeling for creatures who proclaim their right to live is already present in these early collections. The animal world, including insects, is an integral and important part of the landscape for Egan: it expresses the value of life, beauty in complexity.

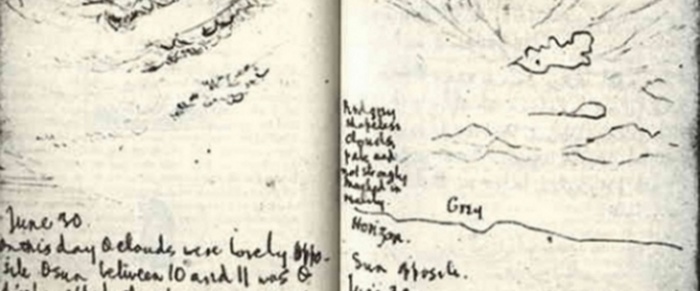

The purely contemplative dimension of the landscape practically never disappears from his entire production.This aspect is felt more intensely, pervasively in a much more recent collection, Epic (2015), Hopkins’ early poems (1864-65) are full of fragments, which almost never become complete lyrics. Looks more like the research of an original poetic language or a need to fix an idea, an object or an emotion, no more than notes to jot down an aesthetic or moral reaction or to fix a word, a phrase perceived as particularly interesting, liable to further development. The memory of the place where Egan spent his childhood and adolescence is the driving force of his collection of 26 poems, to which he gave the title of his hometown, Athlone (1980). It is a microcosm of characters that move and act in every corner of the town or in the suburbs: the great river, the Shannon, with its rhythms, its bridges, its mysterious hidden corners; the canal that runs alongside it and then the streets, each identified in its topography, the alleys, the shops, the castle, the church; and out of the town, the vast plain of the Irish Midland. Everything wrapped up in a calm atmosphere, slightly suffused with melancholy. Egan's is truly a return, a reconstruction, in the landscape of the mind, of places lived and perceived. The intensity of the vision anticipates the sublimation of the landscape into a symbol, beyond sheer memory, and the introduction of myth in his poetry. In Non Symbolist which is part of the Seeing Double collection (1983), the transition to myth has almost been completed:

Non Symbolist

I was jogging down yesterday evening the

ditches growing into a dusk

of December jagged in withered thistles

both sides in a way gleaming off into nightfall

the long slope of a hill a house & a star here and there when the crows lifted

hung on my view floated away and

that’s about it one small moment which could take the biggest words

Despite its programmatic title, it is precisely in this poem that the symbol emerges, suddenly and unexpectedly. The crows are real, but their almost hallùcinatory material substance gives them a dimension that goes beyond the moment, making them, for the common reader, symbolic figures. Precisely in this short lyric the mythical dimension,which will reappear more or less explicitly in subsequent collections, begins to assert itself. Also, for the reader who has some knowledge of Celtic mythology, these verses acquire the inclusiveness of myth, like the crows that soar over a wheat field in the well-known painting by Van Gogh. Hopkins’ first description of a landscape that is not the mere recording of a visual impression can be read in his first great poem, The Wreck of the Deutschland, and it is a seascape! The 13th stanza gives a dramatic description of the ship entering the storm:

The Wreck of the Deutschland

Into the snow she sweeps,

Hurling the haven behind,

The Deutschland, on Sunday; and so the sky keeps,

For the infinite air is unkind,

And the sea flint-flake, black-backed in the regular blow,

Sitting Eastnortheast, in cursed quarter, the wind;

Wiry and white-fiery and whirlwind-swiveled snow

Spins to the widow-making unchilding unfathering deeps. ...

The last four lines of the octave, with their sequence of alliterations chasing one another with a pressing rhythm, of compound monosyllabic and bisyllabic words suggesting precipitation and violence; the key words that close the final lines (blow, wind, snow, deeps), a synthesis of the fury of the elements that drag the Deutschland towards its tragic destiny, have the iconic impact of a nineteenth-century painting of stormy seas and ships tossed by the waves, as in Turner’s well known watercolour “A Ship against the Mewstone at the entrance to Plymouth Sound”. Hopkins no longer repeats such description in the poem, dwelling rather on the moral and spiritual condition of the human beings on board; but the image displayed in that stanza has a lasting influence on what follows. In fact, the whole story, it’s moral value, the emotions of the sailors and nuns, the disturbance of the narrator, all depend on the violence of those few lines. Myth, history, social and political commitment alternate and interpenetrate in at least three collections of Egan’s after 1992, particularly in Peninsula (1992), Famine (1997) and The Hill of Allen (2001). In all of them the landscape is never innocent. In fact those who suffer violence in the years of innocence for a long time carry a scar, which the years often fail to heal. In the same way, a landscape that has suffered or witnessed violence is no longer and often will never be the same: it will have lost the innocence of its natural condition.

In Peninsula the landscape is immediately anthropologically connoted: its inhabitants shape the landscape in the same way that the landscape shapes them. It is a “landscape of tragic faces / where time fades to eternity”. Yet this landscape, so full of history, has a dimension that places it outside of history, gives it the abysmal depth of myth. The onlooker feels like a stranger ("I am an outsider"), the sea, still present, visible, apparently objective, is actually out of his reach ("The incomprehensible sea" (Coosaknockaun). But this same landscape still carries the signs, the wounds of a painful past. Myth, in fact, does not exclude history.

In Dun an Oir"the landscape, witness to the massacre perpetrated by the English on unarmed men, women and children, still holds its cry ("in the crying of these fields"), becomes a witness, and the cliff still screams (" the cliff screams at Ard na Ceartan "); Minard Castle is little more than a quadrangular ruin, but in the perception of the poet, who enters it as it were in its bowels, the castle is still ominously the reference point of a massacre; the silence and peace of the place, in the ears of those who observe and remember, is filled with curses, cries, invocations of a defenseless population overwhelmed by the fury of the English soldiers.

In the 1997 collection, Famine, the poet’s social and political commitment becomes more explicit. It is a sequence, that is a series of poems linked to each other by a single theme: the great famine of the mid-nineteenth century. After more than a century the wounds it caused still affect the landscape. This is explicitly stated in one of the poems of the sequence, number 8: "you can surprise it / [...] in the bitter twist of an old oak // [...] hear it down the empty woods // in the silence of birds wheeling ". Even the stench of those tortured bodies and of those rotting crops seems to persist and mark the landscape: "The stink of famine / ... / you can catch it / down the lines of our landscape". You can read here the first indication of what will become his “ecological” vision of the landscape: “… beauty so / honoured by our ancestors // but fostered now to peasants / the drivers of motorway diggers / unearthing bones by accident / under the disappearing hills”.

Eco-poetry, showing aspects of the same landscape before and after facts or events that caused its metamorphosis, partially contains some of the characteristics we usually associate with political poetry, but with the additional concern for the conservation of the natural balance, a respect for history and the cultural values that have given the landscape its present aspect. It is not a question of conservatism, rather of conscience and responsibility.

The Hill of Allen(2001) is, of all Egan's poetic production, the one that could, with greater approximation, fall into the category of ecological poetry. Faced with the havoc to which the hill — in Ireland’s mythical tales the residence of Fionn Mac Cumhaill and his band of heroes — the poet sets up a sequence of 15 poems plus an epilogue, in which feelings of indignation and historical memories, elegy and tirade, despair and anger alternate and merge in a strict condemnation of a society devoid of values and conscience, ignorant, dominated by the sole concern for the accumulation of wealth and power. What the poet scornfully defines as a "supermarket republic" (poem 2) cannot, because does not want to, understand “whatever Ireland is / whatever culture is / whatever the spirit is / whatever we really are" (Poem 3).

Like degenerate children, those who do not respect the hills, and the Hill of Allen in particular, are deaf to the voices, which rise from them to reproach and plead. In Hopkins’s sonnets of 1877, the landscape is "perceived" rather than described; it is hidden, in a sense, in the folds of a line, in the choice of words, in its rhythm. In "God's Grandeur", for instance, the landscape is implicit: no specific object or place is described, but what the poet contemplates and the reader sees emerges as the sonnet moves on: the world that is charged with the greatness of God is the same world which now appears polluted, soiled by an irresponsible humanity: “all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil". Against this filth stands the infinite variety of nature: the freshness of the morning, made glorious by the spread wings of the Holy Spirit. Also in “Pied Beauty” the landscape is almost a ‘summa’ of the infinite shades of colour of creation. All "counter, original, spare strange" things, which reveal themselves to the eye of the poet, become the concrete manifestation of a spiritual rather than an aesthetic experience and invite to prayer, which is above all praise ("Praise him"). “Binsey Poplars” is a cry of anguish and protest at the cutting down of the poplars, which Hopkins considers equivalent to the destruction of any living being.

Especially interesting in the sonnet is the concern, which today we would define “ecological”, of the responsibility the present generation has towards future generations. A cry against the decline of wild nature is “Inverness”, a poem of 1881. It is an extraordinary piece of bravura. The landscape here becomes language, and the language gives back the sound of a brook “roaring down”, the details of its foam – “a windpuff-bónnet of fáwn-froth” – its colours, the dew on its brakes, the heather, the fern, the mountain ash. A hymn to the wilderness. One of the so-called ‘sonnets of desolation’, “No worst, there is none”, shows a different type of landscape — wild, rugged, dangerous — a landscape of the mind, the landscape of a troubled spirit:

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap

May who ne’er hung there...

The mountains, the “cliffs of fall” of sensitive experience metamorphose into the condition of the spirit: both, memory and symbol, are "frightful". To conclude, the two poets have a different vision of the world, if not opposite, but certainly one important thing in common: for both the landscape is not simply a thing of beauty, an aesthetic experience. It is also that, of course, but it is mainly a spiritual experience, something to be grateful for; and for both this Being to thank, to honour, to admire is the catholic god. Egan's poetry is predominantly lyric with elegiac modulations, Hopkins’s is lyrical-religious with mystical shades, even though a sensual pleasure for “dappled things” is never missing in his poetry, except in the “terrible sonnets”. The landscape is home, memory, history, and myth for Egan; for Hopkins it is part of somebody else's home: God's. It is a gift. His gift.