Literature and Spirituality in Hopkins's Poetry

This Lecture was delivered at Hopkins Literary Festival 2003Michael O'Dwyer,

French Depatment,

NUI, Maynooth, Ireland

The purpose of this paper is to explore the manner in which Christian writers of fiction integrate spiritual themes into the fabric of a literary work. The paper will explore three

ways in which this is done

- use of the diary form;

- use of the epistolary form;

- the symbolic use of space.

1. The Use of the Diary Form

In dealing with the relationship between literature and spirituality and, more particularly, with the problems surrounding the presentation of spirituality in literature a certain clarity in regard to the term "spirituality" and the sense in which we will use it, would appear to be necessary.

When speaking of spirituality or the spiritual we will be talking about what pertains to or affects the spirit or soul especially from a religious point of view.

We will also use the term in the sense of what pertains to or is concerned with sacred or religious things, holy, divine and pertaining also to prayer, churches and clergy.

When speaking of literature and spirituality in the sense in which the term has just been outlined, one is reminded of French literature of the 1930s as many of the issues which were raised in the literature of this period have become hardened chestnuts ever since when this topic is debated.

The question of the so-called catholic novel comes to mind along with some of the problems posed by the use of such a term. The first problem which arises for many people is the notion that the use of the term catholic novel may imply that the novelist is akin to a preacher. This approach puts the emphasis on the content or message of the novel and underpins the danger of reducing the work of literature to a work of apologetics or propaganda. Even if these extreme terms are avoided, there is certainly very often a cite implication that the novel is marked by a didactic approach. This is why we find Mauriac, for example, stating that he is not a catholic novelist but a catholic who writes novels. All the novelists who treated the theme of religion were conscious of this problem. Julien Green who succeeded Mauriac in the Académie française, constantly notes in his diaries that novelists engaging in edifying literature or hagiography are betraying their profession.

Problems such as the above forced the novelists of the 1930s who were concerned with various aspects of spirituality to think through their position and throw some light on what might be conceived as the essence of their role. There are some basic statements, which recur with certain variations when writers like Claudel, Bernanos, Mauriac, Green and the critic, Charles du Bos, discuss the question of the presentation of spirituality in literature.

All repeat constantly that a literary work is to be judged by literary standards ONLY and that any evaluation of the spiritual content of the work must take account of the extent to which it is integrated into the work in literary terms like plot, structure, inner coherence, motif, metaphor, metonymy, image and symbol.

Issues which preoccupy French writers like Mauriac, Bernanos etc:

There is also a constant emphasis among these writers on a harmonisation or integration of genuine human emotion into the tenets of religious faith which may arise.

This leads logically to the next issue which recurs i.e. that writers are engaged in an examination of faith as a lived experience and that more precisely in their role qua writers, they are exploring the essentially dramatic aspects of the experience of grace.

What is of primary interest then to the writers of a literary work is the dramatic potential of the aspect of spirituality which they wish to analyse in their works.

The point of departure common to all of the above writers in their reflections is that faith is not dogma but an adventure or an experience of the absolute. Here we find the Pascalian notion that faith is less a question of knowledge than an experience and a commitment. We are dealing with an existentialist notion of faith.

Faith, as experienced in childhood, is another common factor. There is Green's famous account of his mystical experience of God's love as a child contemplating the stars at night and which recurs in transposed form in many of his novels. The beauty of a starlit sky gives us a glimpse, according to Green, of the indescribable beauty of the world as Adam must have seen it before the Fall. For Green, the starlit night is the vocabulary which God uses to enter into communication with human beings.

Quite obviously, Hopkins's poem The Starlight Night comes to mind. While not wanting to force parallels, one cannot ignore the sense of enthusiasm common to both authors when they talk about this subject, an enthusiasm which is reflected in Hopkins's use of sixteen exclamations in fourteen lines. Just as Green evokes thoughts of the Redemption as we have seen, for Hopkins their beauty was bought back by Christ's redemption. The beauty of the stars and prayers and alms, the means of reaching God, are identified. The heavens themselves are but a reflection of eternal beauty. The stars are an edifice, the home of Christ and Mary. It is interesting then to note how both writers in their own way, through an enthusiastic evocation of the beauty of a starlit night, arrive at the conclusion that this beauty is linked to God's redemptive love.

Children, Evil and Grace

Children play an important role in representing grace and resistance to evil, while in Mauriac's novels and in those of other Christian writers childhood is a metaphor for Christian virtues such as humility.

For novelists in this mould the question of the relationship between the natural and supernatural is obviously important. There is, very often, a sense of continuity from one to the other as in the examples which we cited from Green and Hopkins where the world of nature reflects and reveals the glory of God.

Sometimes, however, the whole drama of a work can arise from a contrary experience. The protagonists may feel confronted with what is most intolerable in their inner being and thus feel cut off from the absolute, supernatural or love of God and feel enclosed in their human environment as in a prison. This is the mental state which forms the drama of Mauriac's Thérèse Desqueyroux and which is at the basis of elements of the spiritual crisis of Bernanos's country priest. This sense of rupture with the supernatural world is sometimes an inherent part of the spiritual quest of the characters whom one finds in so-called Christian novels and plays. Characters in these novels very often find themselves moving between extremes, moving from an elated spiritual experience to the other extreme of despair and a sense of void.

Here the novelist is e xploring the dramatic potential inherent in the risk of faith. Bernanos is particularly adept in plumbing the depths of this state of soul.

The Conflict Between Good and Evil

The basic drama in a literary work dealing with Christian themes is, of course, the conflict between good and evil. The manifestation of evil can take many forms. For Bernanos, evil tends to be situated in an area which transcends the usual moral categories such as honesty or sexuality. Evil is to be found in a sense of nihilism or despair which seems to absorb or subsume other categories of sin. For this reason, the experience of Gethsemane, or the sense of total solitude or the suffering of the soul abandoned by God feature prominently in his novels. The Curé of Torcy in his Diary of a Country Priest, for example, states that he always finds himself in the Garden of Olives. This is the drama of Christian life at its most intense, the abandonment of the soul by a loving God and the consequent experience of silence and emptiness.

In the novels of Mauriac and Green, on the other hand, evil can be pinpointed to specific areas or categories such as sexual mores. The drama or conflict between sin and grace is then presented as a conflict between body and soul, flesh and spirit with sudden movements from the joys of a spiritual experience to the expression of the fulfilment of carnal desire as in Greens's Moïra.

A similar conflict can also be deciphered in Hopkins's temperament, as, for example, in his confessional notes when he accuses himself of being too much drawn to choristers or fellow undergraduates or of looking too long and admiringly at a married woman.

Many years later, on January 30, 1968, Green quotes Hopkins who talks of his great admiration of physical beauty and who also says that it is a great consolation to find beauty in a friend and a friend in beauty. However, Hopkins also adds that this kind of beauty is dangerous. Having raised the question why? Green comments that beauty as depicted in the Angélique of Ingres and the naked war heroes of David can pose moral problems. What makes this drama more poignant in iterary terms is the consequence of this state. The consequences of decisions taken by the characters have an eternal dimension. The soul is not only faced with a conflict between hope and despair, flesh and spirit, but also the p ossibilities of eternal happiness or damnation. This aspect of the potential for literary drama is one that is unique to Christian writing.

The Communion of Saints

An important aspect of Catholic dogma which underpins the writings of Bernanos, and to a lesser extent, those of Mauriac and Green, is the doctrine of the Communion of Saints or the reversibility of merits. This doctrine establishes that God and the people whom he has created are united in an interchange of grace. The dead may help the living, saints may help sinners and atonement for wrongdoing can have eternal consequences. In this scheme of things the experience of sin can sometimes be an opening towards a spiritual world. There is ample scope here for the artist to explore the literary richness and c omplexity of the circulation of grace in a world in which the destinies of living and dead, saints and sinners are intertwined.

The characters in a Christian novel or play are part of a grand design within which they try to find their place and its significance. They wander in a labyrinth of obscure and mysterious paths which lead them to or turn them away from God. They advance between two abysses, good and evil. For them, there is an absolute in relation to which everything else acquires its meaning. The lives of the characters are firmly placed in the perspective of the eternal. They express a hunger and desire which most people choose to ignore, c onsciously or unconsciously, by immersing themselves in a state of Pascalian divertissement. The novelist or dramatist will try to take us within the consciousness of characters coming to grips with temptations towards revolt and despair in a quest for the absolute which often assumes tragic dimensions.

The Christian novelist and dramatist can thus be seen to explore the consciousness of characters for whom fulfilment is represented by divine love. The good artist will exploit the complexities of this quest for the absolute with its alternating moments of fulfilment and void, linearity and discontinuity in the meanderings of a human existence which is shot through with possibilities of embracing a divine presence. The writer's imagination must seek out the signs of the supernatural or the mystery of the absolute and the relative, which are, in the Christian scheme of things, at the heart of the human condition as a consequence of the doctrine of the Incarnation.

How is the Writer to Probe the World of Grace - without playing God?

The question then is how the writer is to probe this world of grace, this intimate and mysterious relationship between the human and divine without f alling into the trap of playing God with his characters, an accusation which was sometimes levelled against Mauriac. This raises a question which Green finds interesting in Hopkins i.e. the ineffable character of beauty and the difficulty of expressing it in language. He finds Hopkins's language bizarre, belle et forte as he desperately tries to express what man has seen in some form of earthly paradise.

He concludes that Hopkins seems to be trying to express something that goes beyond language. Green always displayed a great awareness of the limits of verbal communication especially in regard to its capacity to express the mystery of a person's inner life and its relationship with the divine. In this context he sees music as being a superior form of art. In an entry to his Journal on January 16, 1990, he states that music expresses in sublime airs and with unparalleled inspiration what the words of a poem can never express. The challenge for the writer is to proceed with the acceptance of the limits of his knowledge and powers of expression in regard to the intimate workings of grace. He must respect the complexities governing human psychology and behaviour and also the conventions governing his trade i.e. the conventions governing creative literature.

These are the challenges facing Christian writers as they endeavour to present the human struggle with the spiritual or the supernatural with human and literary credibility. In facing these challenges and in endeavouring to present the drama of Christian living in credible human and literary terms writers will avoid the pitfalls of omniscience, apologetics, abstraction, hagiography and propaganda of which they have often been accused. The real challenge for Christian writers is, in the words of Mauriac, to present in flesh and blood what the theologian presents in the abstract.

The Word and words

This notion of literary incarnation is also highlighted by Charles du Bos when he describes the incarnation which takes place in literature as the living flesh of speech. All literature, for du Bos, is incarnation and in literature this incarnation takes place thanks to the living flesh of words. He adds that whereas in the sacred mystery the word was made flesh, in the profane mystery the creative emotion, that emotion which, when incarnated into form, manifests at its highest and at its most complete the personality of the artist, is made flesh in words.

For du Bos, emotion is the living soul and words are the living body of literature. He adds that great writers and great artists have always been more or less conscious that literature and art are an incarnation but few have been conscious of the fact that their words are related to the Word itself. It is this relationship between the Word and words which is at the heart of the Christian novelists' task as they deal with various aspects of spirituality.

How the Christian Writer gives Credibility to their explorations of the Spiritual Christian writers have, over the years, adopted various techniques which serve to give credibility and verisimilitude on the human and literary level to their exploration of spirituality.

Epistolary Form: a technique for the Novelist to Explore Spirituality

One technique adopted by these writers is the use of the diary form. This is not an uncommon form in the history of the French novel. Indeed, since 1803, one can point to at least 114 novels which are either entirely in diary form or which contain extracts of diaries at critical moments in the unravelling of the story. In the domain of Christian writing one may point to Gide's La Porte Étroite and La Symphonie pastorale, Mauriac's Le Noeud de vipères, Bernanos's Journal d'un curé de campagne, the final volume of Roger Martin du Gard's Les Thibault and Green's Varouna.

One of the problems facing a novelist like Bernanos is that he is trying to show sanctity from within. The diary form can be helpful in this regard in that the readers see the creative process taking place before them. They are witnessing the production of a text and the various lacunae and references to editorial processes and manuscripts serve to give greater verisimilitude to the spiritual struggle which forms the subject of the book. The author and narrator are not identical and this confers a greater impression of an independent existence to the protagonist.

A greater variety of point of view is often given to the diary text with the introduction of letters and dialogues. In non-fiction diaries dialogues are not common. The characters in fictitious diaries are, in general, solitary figures, like Bernanos's Curé and Mauriac's Louis in Le Noeud de vipères. The characters are generally trying to come to grips with periods of failure and depression in their lives. They are also usually people who have achieved a certain level of education and are surrounded by characters with whom they have some difficulty in identifying.

The diary form can be described as a mirror in which the protagonist is struggling to get to know himself or herself. The diarists are at one and the same time, author, reader and character in their own texts. The other characters are also mirrors in that, very often, their role is to reveal differnt aspets of th tempeamet f the protagonist.

The diarists are trying to construct an image of themselves in words. They are trying to establish an identity and to penetrate to the deeper self which lies beyond the world of appearances. There is a search for a harmony with a deeper self and, in the case of Mauriac and Bernanos, with God. There is a high degree of self-judgement and, like Bernanos's Curé the protagonists often declare their intention to reread their text with a view to deriving some benefit from it; one may see how this type of introspective setting lends itself easily to descriptions of examination of conscience and analysis of intimate moral issues and the question of the relationship between the individual and a divinity which often follows from questions of personal identity and reflections on the r ole of the individual's place in the world.

Strong parallels in the Writing of Gerard Manley Hopkins We can see here the close link between the questions which may be raised in fictitious diaries and those raised in Hopkins's confessional notes. All these characteristics are to be found in the diary of Bernanos's curé for whom the writing of the diary is not only a form of examination of conscience, but a continuation or extension of his prayer life, the essence of which for him is a conversation with Christ. The self-examination process on the part of Jeanne, the protagonist-diarist of the third part of Green's Varouna leads to an opening towards the spiritual and the diary closes with the words of the Pater Noster coming to her lips.

There is a similar opening towards the supernatural and the world of grace on the part of Louis, the protagonist-diarist of Mauriac's Le Noeud de vipères.

These are some examples of how the diary form with its probing on the part of the protagonists of the depths of their consciousness and conscience, the movement from past to present, the desire to change their lives, lends itself to the possibility of a credible treatment in psychological terms of the questions of man's relationship with God and the quest for grace and salvation.

Dealing, as most diaries do, with the desire for better self-knowledge on the part of a solitary character, the diary form is almost a natural form for probing the constancies and vicissitudes of the interior or spiritual life and for placing human life in the perspective of the eternal.

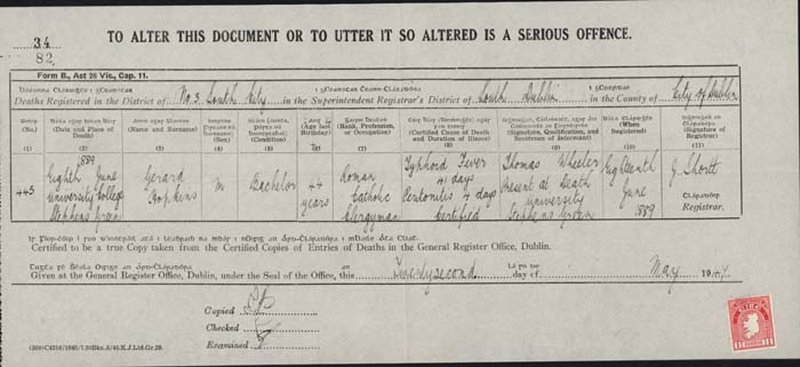

Hopkins's second note-book, begun on March 25, 1865 deals with such issues as it is a daily record of his moral and spiritual life.

The Epistolary Form - a tool for the Christian Writer

Another technique used by Christian novelists to explore the inner depths of the spiritual lives of their characters is the letter form; this form is by no means a modern one, and neither is it by any means confined to Christian writing. The letter as a narrative vehicle can be found in the works of Ovid, Cicero and Quintilian; in the later Middle Ages we find the form in the works of Christine de Pisan and at the boundary of the Enlightenment and Romanticism the supreme example of the use of this form is Rousseau's La Nouvelle Héloïse. The epistolary form, as Mme de Staël puts it, is appropriate to the observation of what is taking place in the heart. The letter gives a polyphonic or multivoiced dimension to the novel, a dimension which was greatly appreciated by Dostoïevsky. The use of the letter form makes for a greater variety of perspective or focalisation and can become a credible technique for revealing the intimate details of the inner life of a character, details which should normally be outside the domain of an omniscient narrator. The letter form can then add greater artistic subtlety and variety of viewpoint to the narrative. Gide, for example, uses letters at critical moments when characters have important confessions or admissions to make about themselves. This gives a dramatic dimension to the texture of the work. Other effective uses of letters from a literary point of view in a more precisely Christian context may be seen in the novels of Bernanos, Mauriac and Green

. In Journal d'un curé de campagne, there is the letter written by Mme la Comtesse to the curé and which he receives after her death. Mme la Comtesse has had a gruelling encounter with the curé in course of which he leads her to come face to face with the sin of revolt against God for the loss of her child and the consequent sin of despair. The letter gives us a credible insight into the state of the Comtesse's soul after the encounter i.e., her admission that she was moved by the childlike simplicity of the curé and her intention of confessing her sins and being reconciled with God.

One of the most moving examples of use of a letter is towards the end of Mauriac's Le Noeud de vipères, when the old man, Louis, who has lived in isolation, from his family and who has felt unloved, discovers a letter written by his now deceased wife which reveals her love and attachment to him.

In Julien Green's Moïra the puritanical and scrupulous Joseph Day finds himself locked in a room with his seducer, Moïra, who is compared to harlots in the Bible. For our knowledge of what is happening, we are dependent on a letter which Moïra decides to write to a friend. The letter reveals that Moïra is moving from being a pleasure machine to use her own expression, to a feeling of genuine human love for the innocent Joseph.

The letter is an intermediary text situated between narrative and discourse, mingling a written and oral style and becomes an appropriate vehicle for the expression of inner emotion and spirituality.

The letter allows for the effective expression of the hesitations or the fluctuation of the thoughts and emotions of the characters and once again can be seen as a credible literary manner of probing the spiritual drama of the life of a character.

Spatial Connotations, an additional tool for the Christian Writer

Another technique used by Christian novelists to suggest the role of the supernatural or spiritual in their works is the use of space. Spatial connotations are constructed and transformed in such a way as to suggest or symbolise the inner lives of the protagonists. Spatial descriptions give rise to an inner landscape through a metaphoric and metonymic use of spatial terminology. Topographical references are linked to the inner drama of the work and can assume spiritual and eschatological significance. Descriptions of nature and of the changing of seasons are generally highly symbolic in the works of Christian writers including Hopkins.

Archetypal images such as water, night and the sky have also been effectively and poetically used by Christian writers to denote the fusion of the human and divine which is at the heart of the drama of the work.

Conclusion

How to 'render the supernatural natural' We have, in this presentation, concentrated on three ways in which Christian novelists have tried to present a spiritual drama in credible psychological and literary terms. By means of the diary form, the epistolary form and the symbolic use of spatial connotations Christian writers have tried to avoid the problem of playing God with their characters. A more detailed presentation might also have looked at the technique of intertextuality in the use of Biblical references and references to other classic spiritual texts by these writers in their efforts to communicate a Christocentric view of the world or to "render the supernatural natural" to use Mauriac's description of Bernanos's literary world.

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2003

- Scottish View of Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Explore other areas of The Hopkins Archive

- Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Climb to Transcendence

- Hart Crane and Gerard Manley Hopkins

- How Father Hopkins SJ Prays

- Oscar Wilde and Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Flannery O Connor and Hopkins

- Levelling with God

- Polish writer Norwid and Hopkins influence

- Walker Percy and Gerard Manley Hopkins