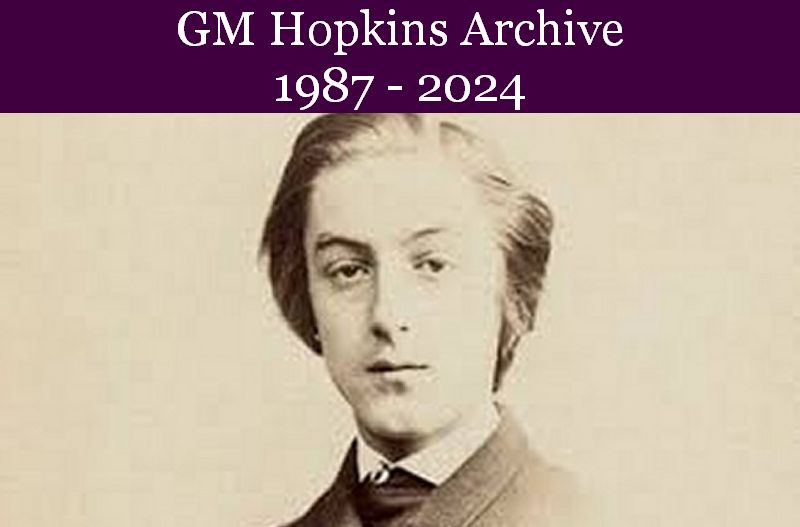

Hopkins' Friends in Dublin

Michael McGinley

Let us begin with something new - a quotation dated 11 June 1889 from a diary:

I had a very busy day as in the morning I had to assist at the office for poor Fr Hopkins, SJ. But a few weeks ago he and I were walking together: this time I have escaped.

This diary was kept by Fr. Richard Colohan who had taught classics at Clonliffe College. In 1888 he was serving as a curate in St Kevin's parish based in No 83 Stephens Green and ministering in Newman's University Church on the Green. The historian Brendan O Cathaoir drew my attention to this diary. He discovered it while editing a history of Bray parish where Fr. Colohan later served as parish priest. Brendan also noted that Hopkins enjoyed visiting Fr Colahan's mother and sister in Dalkey, Co. Dublin. Prompted by the diary entry Desmond Egan suggested that I write a paper on Hopkins' various Dublin friends. It may be useful to recall here some of his ambitions as he undertook this major turning in his career, his time in Dublin.

Hopkins's major ambitions in 1884

1. His priesthood - His relationship with God was central to Hopkins' being. This was played out in the framework of the Jesuit discipline.

2. His job in Dublin. In 2014 Lesley Higgins and Michael F. Suarez, S.J. edited Hopkins' Dublin Notebook which clearly shows that Hopkins fulfilled his university duties with care and expertise.

3. Poetry - his own and his detailed advices to Bridges, Dixon and Patmore. It is well to recall here Hopkins' comments on inspiration. In a letter to Baillie dated 10 September 1864 he says:

The word inspiration need cause no difficulty. I mean by it a mood of great, abnormal in fact, mental acuteness, either energetic or repetitive, according as the thoughts which arise in it seem generated by a stress and action of the brain, or to strike into it unasked.

4. Dorian measure - Hopkins planned to write a major original book on the metre of the Greek lyric choruses. This required not only deep involvement with classical Greek literature but also the deployment of sophisticated mathematical tools which Hopkins lacked.

5. Music - Hopkins composed at least 27 settings for poems. In a letter to Bridges of 18 – 23 June 1880 he says:

I wish I could pursue music; for I have invented a new style, something standing to music as sprung rhythm to common rhythm; it employs quarter tones. I am trying to set an air in it to the sonnet 'Summer ends now'.

And on 11 – 12 November 1884 he added:

.Before leaving Stonyhurst, I began some music, Gregorian, in the natural Scale of A, to Collins' Ode to Evening. Quickened by the heavenly beauty of that poem I groped in my soul's very viscera for the tune and thrummed the sweetest and most secret catgut of the mind. What came out was very strange and wild and (I thought) very good

Hopkins's Psychological Make-up

Hopkins experienced the great highs and lows sometimes seen in people of genius. In a letter of 26 – 28 October 1880 when he was a curate in Liverpool, Hopkins explains his delay in answering a letter from Bridges,

I could never write; time and spirits were wanting; one is so fagged, so harried and gallied up and down. And the drunkards go on drinking, the filthy are filthy still would that I had seen the last of it.

In Ireland Hopkins increasingly suffered low moods. An intriguing question arises - would he have experienced the highs that so glowingly shine in his poetry if he had not also plumbed the dark depths of his soul?

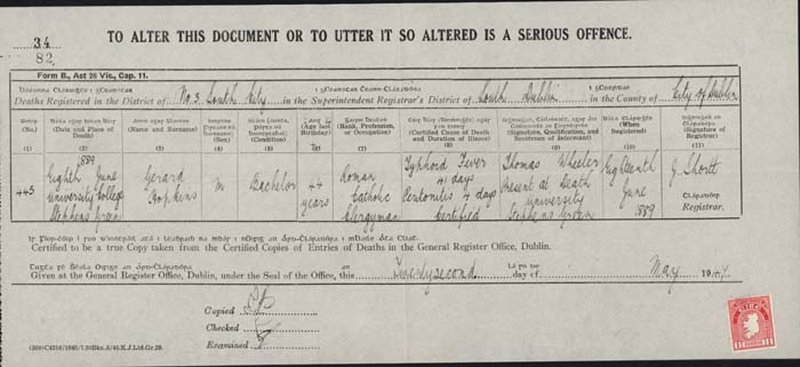

Hopkins in Dublin

Much of the writing about Hopkins in Dublin is based almost exclusively on analysis of the so-called sonnets of desolation written probably in 1885 – 86. It is well to recall, however, that in these poems there is light and even some hope in the gloom. In To seem the stranger Hopkins asserts Not but in all removes I can Kind love both give and get. And in “Patience, hard thing there appears the comforting lines ¦ Natural heart's-ivy Patience masks Our ruins of wrecked past purpose.

In focusing on Hopkins' Dublin poetry it is important not to ignore his social life in the city. His many friendships present a comforting picture of someone not lacking in ambitions for his great powers.

Hopkins' Dublin Friendships

Hopkins moved in many different circles in Dublin - the Jesuit community, academic circles, the literary and artistic scene in Dublin, recreational activities and contacts with families in the city.

The Jesuit community

Apart from the strong Jesuit presence in University College there were many other Jesuit houses which Hopkins visited, notably Clongowes Wood College in Co. Kildare, St Stanislaus College in Co Offaly and Milltown Park in Dublin. Hopkins greatly valued the help and friendship of Fr. William Delany, President of University College. In a letter to his mother, dated 26 November 1884, Hopkins says,

>Fr. Delany has such a buoyant and unshaken trust in God and wholly lives for the success of the place. He is as generous, cheering, and open hearted a man as I ever lived with. Fr. Delany was more than a friend.

He was alive to Hopkins' delicate constitution and took care he got more than the usual holiday breaks when his spirits were at a low ebb. But Hopkins' greatest friend in the Jesuit community was Robert Curtis. In the same letter to his mother he goes on to say,

And the rest of the community give me almost as much happiness, but in particular Robert Curtis, elected Fellow with me, whom I wish that by some means you could some day see, for he is my comfort beyond what I can say and a kind of godsend I never expected to have. His father, Stephen Curtis Q. C., and mother live in town and I often see them and shld. more if I had time to go there.

On 2 March 1885, again writing to his mother he says of Curtis – to see him (or know him) is to love him. Robert Curtis, born in 1852, was eight years younger than Hopkins. He was a gifted mathematician who had graduated with distinction from Trinity College Dublin. He entered the Society of Jesus in May 1875, but due to his epilepsy he did not become a candidate for ordination. He joined the newly-founded University College in the faculty of mathematics and science and was named Royal University of Ireland Fellow in Natural Science in January 1884 when Hopkins also became a Fellow. Curtis was known for his sense of humour and was keen on swimming and walking. Curtis and Hopkins hiked in northern Wales in September 1886. Hopkins wrote about, described this Welsh holiday in letters to Dixon and to his mother. In a letter to Dixon he refers to

this remote and beautiful spot, where I am bringing a pleasant holiday to an end. (Curtis), my companion and colleague left me last night, being called to Dublin on University business.

He paints a fuller picture in a later letter of to his mother written from Dublin:

Our holiday was most pleasant and serviceable … we were a week at Caernarvon and another at Tremadoc We ascended Snowdon and had a beautiful day. We walked ever so much. We went up the toy railway to Blaeneau Ffestiniog and enjoyed it We saw Pont Aberglaslyn, the beauty of which is unsurpassed, and I saw the Pass of Llanberis and Beddgelert. I preached two little sermons. The holiday has been a new life to me - I am even getting on with my play of St. Winefred's Well.Hopkins, no doubt, experienced Thomas Moore's insight - how the best charms of nature improve / when we see them reflected in looks that we love.

In August 1888 they toured western Scotland. This holiday was less of a success. Hopkins wrote to Bridges:

Six weeks of examinations are lately over and I am now bringing a fortnight's holiday to an end. My companion (Robert Curtis) is not quite himself or he verges towards his duller self and so no doubt do I too.. We are in Lochaber and have been to the top of Ben Nevis and up Glencoe on the most brilliant days, but in spite of the exertions or because of them I cannot sleep and we have got no bathing (it is close at hand but close also to a highroad) nor boating and I am feeling very old and looking very wrinkled.

Later in the letter Hopkins mentions that “I will now go to bed, the more so as I am going to preach tomorrow but goes on with cheerful comments on books , Handel, cricket and Darwinism and Dublin friends. It is clear, taking the smooth with the rough, that Curtis' enduring friendship with Hopkins was central to his wellbeing.

Wider academic circles in Dublin

As an Oxford graduate Hopkins had free access to the library at Trinity College. This was particularly useful as University College had lost its library to Clonliffe Seminary when the Irish bishops entrusted the running of University College to the Jesuits. Hopkins had high ambitions for his musical compositions - he was already envisaging settings for orchestra and choirs. He sent Dixon and Bridges examples of his work. Writing to Bridges on 11 – 12 November 1884 he says,

You saw and liked some music of mine to Mr Patmore's Crocus. The harmony came in the end to be very elaborate and difficult. I sent it through my cousin to Sir Frederick Gore Ousely for censure and that censure I am awaiting.

Ousely had been Professor of Music at Oxford since 1855 – a well known composer and writer on music. Hopkins also sought out Sir Robert Stewart, Professor of Music at Trinity College, with whom, after a rocky start, he became friendly. Stewart, born in Dublin in 1825, became Professor in Trinity in 1862. His personal attractiveness, his masterful playing of the organ, his skilful improvisations, and his prodigious memory won him many friends and admirers (Thornton and Phillips, 2013). He was knighted in 1872. In a letter of 2 November 1884, Hopkins tells his sister Grace of his first meeting with Stewart,

I have made the acquaintance of Sir Robert Stewart, who has a pleasant hearty undisguised snubbing way and has lent me his lectures. I made Sir Robert's acquaintance (we were intimate in about you count forty) in the great hall of the Royal University as degrees were being conferred, including nine lady bachelors.Sir Robert is a great admirer of Purcell does not believe in Greek music, nor in some other things that are good But for all that I like him and hope to know more of him.

In a later letter to Bridges nine days later he reports that Stewart “a learned musician of this city, much given to Purcell, Handel and Bach†said that a treatise on harmony by John Stainer was the most scientific treatment he had seen.

Letters from Stewart to Hopkins shows how their friendship matured. On 22 May 1886 Stewart addressing Hopkins as My dear Padre opens with some teasing comments on a musical performance which he had not attended. He continues

Indeed my dear Padre I cannot follow you through your maze of words in your letter of last week. I saw, ere we had conversed ten minutes on our first meeting, that you are one of those special pleaders who never believe yourself wrong in any respect. You always excuse yourself for anything I object to in your writing or music so I think it a pity to disturb you in your happy dreams of perfectability -- nearly everything in your music was wrong -- but you will not admit that to be the case -- What does it matter ? It will all be the same 100 years hence

In a further letter after this mauling Sir Robert addresses Hopkins as Darling Padre he continues

you are impatient of correction, when you have previously made up your mind on any point, & I R. S. being an Expert you seem to me to err, often times, very much.

He goes on to point out elementary errors in Hopkins' composition. On 11 June 1886 Hopkins reports to his mother that his setting for Who is Sylvia? was to be performed with some corrections at a concert in Belvedere College. It was not, in fact, performed

Hopkins' relationship with Stewart developed despite these early rebuffs. Writing to Bridges in October 1886 he reports that

Talking of counterpoint, good Sir Robert Stewart of this city has offered to correct me exercises in it if I wd. send some: I have sent one batch.

On perhaps 30 October 1886 (the date is uncertain) Stewart wrote to Hopkins addressing him this time as Dear Father! saying that he had not had time to look at your Theses till the 30th adding,

I mark all I dislike, you are very much improved, I rejoice to say. Don't choose a tune again with long skips . Don't separate Alto and Tenor: This is bad . After some more technical advice he concludes: Can you play pianoforte at all? If so get Bach's 48 Preludes and Fugues¦. if you were my son instead of my Father I could give you no better advice than to study and play this incomparable work!

Unfortunately Hopkins never mastered the piano. He tells Bridges on 6 October 1886 of two tunes he wrote,

I had one played this afternoon, but as the pianist said: your music dates from a time before the piano was. Two choristers, who were at hand, sang the tune, which to its fond father sounded very flowing and a string accompaniment would have set it off.

On 23 December 1886 Stewart sent a short letter to Hopkins drawing attention to technical faults in his counterpoint and chromatics and ending

I am going to London on Monday night to get rid of a bad cough. Adieu, padre mio! It is clear that their acquaintanceship had begun to flower into friendship.

On 25 – 6 May 1888, Hopkins tells Coventry Patmore that he had some good luck when he made another attempt to set his tune to Patmore's Crocus in strict counterpoint and sent it to my friend Sir Robert Stewart>Sir Robert's verdict amounted to saying that it was successful. In high elation he wrote to Bridges on 13 – 14 September 1888:

My stars! Will my song be performed?¦ a most ambitious piece and hitherto successful but suspended for want of a piano this long while. You could not help liking it if even Sir Robert Stewart unbent to praise it (the most genial old gentleman, but an offhand critic of music and me).

There is a touching sequel to the Hopkins-Stewart friendship. Almost a year after Hopkins death his mother wrote to Sir Robert to enquire if he had any writings of her son. On 9 May 1890 he replied saying he had not. He added,

He and I were a good deal together, I found out that he had a great penchant for the art called Counterpoint, so little known and little studied by amateurs & I offered to look over his exercises without charging him anything -- for I thought it a pity that his religious position although an educated and refined man, a position possibly including something like a vow of obedience & poverty -- should interfere with the exercise of a delightful pursuit, like that of Music. I was much attached to your son, & fancy I can now behold his saintly expressive face.

She sent him a photograph of Gerard and on 14 May 1890, he wrote to thank her,

I am very much pleased to get your dear, gentle, clever son's photograph I thought they [the Jesuits] worked a delicate man like him far too much. Once more, thanking you for your thoughtfulness in sending me the picture, which I shall always preserve & value very much.

The literary and artistic scene in Dublin

The art studio of John Butler Yeats at No. 7 St Stephens Green was an important venue for writers and artists in Dublin in the 1880s. It was at the Yeats studio, less than five minutes walk from University College that Hopkins first met W. B. Yeats (probably once) and the poet Katherine Tynan. Miss Tynan, fourteen years younger than Hopkins, was sitting for her portrait by John Butler Yeats. Father Matthew Russell brought Hopkins to meet her there early in November 1886. Russell was, in Tynan's words the reconciler: Everywhere he touched, he dispelled a prejudice.

Fr. Russell established the Irish Monthly in 1873 which contributed to the Irish literary revival, publishing, among others, W. B. Yeats, Oscar Wilde and Katharine Tynan. In 1886 he took charge of the small number of residential students in University College. He developed contacts with a wide range of intellectuals as well as visiting the poor in the Dublin slums. Katherine Tynan, the fifth of twelve children, lived in Clondalkin, five miles from the city centre. Her father was a prosperous farmer and cattle dealer. He encouraged his daughter's precocious poetic talent. Fr. Russell was a significant ally of Katherine and her poems appeared in the Irish Monthly and in many other journals. Her first volume of poetry – Louise de la Valliere and other poems - was published in 1885 and sold widely. Russell sent a copy to Cardinal Newman who sent his compliments to Tynan. She developed a close friendship with W. B. Yeats who admired her work. In her Reminiscences, published in 1913, Tynan describes John Butler Yeats and his studio circle. There was, she recalled, a great foregathering there. Yeats talked about his theories of painting. In Memories published in 1924 she recalls Fr. Russell bringing Hopkins to the studio.

Fr. Hopkins talked much of Robert Bridges, his great friend, and afterwards came with Fr. Russell to see me at Whitehall, bringing the privately printed volumes of Bridges' poems. That day in Yeats' studio, Fr. Hopkins brought an air of Oxford with him, small and childish looking, yet like a child sage, nervous too and very sensitive.

Hopkins' friendship with Tynan flourished. She wrote to him on 6 November 1886 thanking him for sending her three books by Bridges:

I wish you had written in them; it would have given them double the value in my eyes, but some day perhaps you will do that too for me.. I wonder how you and Mr Yeats finished the discussion on finish or non-finish. I hope you like Mr Yeats, because I like him and think him so true an artist. It has been a real pleasure to me to meet you: I hope I may have that pleasure again. With Kindest regard and thanks

Tynan reported to Hopkins that Yeats was greatly delighted with the visit but lamented that Hopkins with all his gifts for Art and Literature should have become a priest. Hopkins commented You wouldn't give only the dull ones to Almighty God.

Hopkins would probably not have received Tynan's letter of 6 November when he wrote on 7th November, 1886 to Coventry Patmore saying

I seem to have been among odds and ends of poets and poetesses of late. One poetess was Miss Kate Tynan, who lately published a volume of chiefly devotional poems, highly spoken of by reviews. She is a simple bright-looking Biddy with glossy very pretty red hair, a farmer's daughter in the County Dublin. She knows and deeply admires your Muse

On 14 November 1886 Hopkins wrote to Tynan to say that Bridges had published some other thing. He added

Some of the short lyric poems have the exquisiteness of Herrick and of more earnest feeling. I send one favourite. This poem began Thou didst delight my eyes

Writing to Bridges on some three weeks later, on 26 November, Hopkins says

My marketing of your books brought in admiration everywhere I enclose the gentle poetess Miss Tynan's letter of 6 November.

On 11 December Hopkins informed Bridges that

Professor Tyrrell of Trinity expresses his deep admiration of your muse . So too young Mr. Gregg. So too Miss Tynan. But perhaps these two are fry.

On 27 December 1886 Tynan wrote to Hopkins wishing him the compliments of the season adding

I hope sometime to see you again. I enjoyed my one talk with you genuinely, and it would be real pleasure to me if I thought I might hope for a repetition. Perhaps when the Spring makes my cottage lovely you would come with Father Russell to see me? .Mr Yeats has not yet returned; he seems to be getting a great deal to do in London…. I don't know if he has seen your brother.

The reference to Hopkins' youngest brother Everard suggests that Everard was in contact with the Yeats family in London. Later in 1887 Lollie Yeats with six friends produced by hand an artistic journal called The Pleiade which first appeared at Christmas 1887.

It contained an illustrated piece by Everard Hopkins - an appreciation of Frank Potter, an eminent water colourist who died in May 1887, a close friend of John Butler Yeats.

On 27 – 29 January 1887 Hopkins wrote to Dixon from whom he had not heard for some time. Following descriptions of his own activities over a severe winter he concludes,

I have made the acquaintance of a young and ingenuous poetess Miss Kate Tynan, a good creature and very graceful writer, highly and somewhat too highly praised by a wonderful … unanimity of the critics; … she lately wrote me a letter which for various reasons I am slow to answer and as long as I do I cannot help telling myself very barbarously that I have stopped her jaw at any rate.In a much quoted letter to Bridges of 17 – 18 February 1887 in which he laments his three hard wearying wasting wasted years in Ireland. He notes:

I met the blooming Miss Tynan again this afternoon. She told me that when she first saw me she took me for 20 and some friend of hers for 15; but it won't do.On 2 June 1887 Hopkins wrote to Tynan thanking her for sending him her elegant new volume of poems Shamrock.

The reading of the earlier pages gives me the impression of a freer and surer hand than before. This being my busiest time of year I cannot now write more; but when I meet you there is a metrical point I should like to remonstrate with you upon ...He had had difficulty arranging a visit in Spring and wrote to Tynan on 8 July 1887

I have promised to visit a sick man in Howth and that is what I must first do. If later I should find an evening I will try and reach Whitehall. I do not think to concert anything with Fr. Russell: our conveniences would then have to wait on one another. I expect in August to go to England for a short while and if I do not see you before then still I might after. I now see what an ungraciously worded note I am writing, which yet I must send and make things better (or worse) by word of mouth.

Hopkins wrote at some length to her on 15 September 1888,

Thank you kindly for the elegant photograph you have sent me. It does not represent you quite as I think of you (Mr. Yeats' portrait does that) it is however both a faithful likeness and a pleasing picture .

He then gives detailed complimentary comments both on the content and style of the poems published in the volume Shamrocks comparing certain features with the Rossettis, Swinburne and Wordsworth.

The Hopkins-Tynan friendship had proved enriching for both of them, although not without its inhibitions.

Recreational activities

Apart from his walks in the countryside often with Robert Curtis, S.J, Hopkins also made full use of the trains from Dublin to explore the more remote parts of Ireland during short breaks from the University. While visiting the Blake family at Furbough House he explored nearby Connemara, finishing with a boat trip to see the Cliffs of Moher from the sea.

In Dublin, the trams were still horse-drawn. Hopkins liked the Phoenix Park where he did some sketching. In his letters there are glimpses of some of his friends who also joined him on the hills around the city.

Writing to his mother on 2 March 1887 to wish her a happy birthday he says:

Dublin is very dull and one of my best friends, an old Stonyhurst pupil, Bernard O'Flaherty, is going to leave and live in the country. He has constantly called on me and taken walks with me ever since I have been here, which is the highest compliment he could pay me, and now I am every minute expecting him for a last one. I have another great friend Terence Woulfe-Flanagan, who was an undergraduate at Oxford when I was a curate there. These two young men are not Nationalists at all, which, as things go, is a relief.

Woulfe-Flanagan qualified in medicine in Dublin and practised in Chelsea. O'Flaherty joined his father in his solicitor's practice in Enniscorthy where he worked until his death in 1929. Hopkins did not lose touch with him. He told his mother on 26 April 1887:

In Easter I was down with my old pupil Bernard O'Flaherty at Enniscorthy in Co. Wexford. Weather cold but bright, country beautiful, and the people very kind and homely.

The names of Fr. Colahan, mentioned at the start of this paper and perhaps some other walking friends do not crop up in those of Hopkins' letters which have survived.

Families

Hopkins was also on terms of close friendship with some families. Fr. Delaney, President of University College, introduced him to the Cassidys of Monasterevin and he was a welcome visitor there on several occasions. He stayed sometimes with the O'Hagan family in Howth:

The kindest people

He also visited Lord Emly (William Monsell), a prominent Liberal peer who became Vice-Chancellor of University College on 1885. Hopkins also kept contact with the families of some of his Dublin friends, notably with the Curtis family and the mother and sister of Fr. Colahan in Dalkey. It was with the MacCabe family in Donnybrook that Hopkins developed the closest ties. They had been greatly impressed by a sermon of his in Stonyhurst where their son was a pupil and when he came to Dublin they invited him to visit. At one stage Hopkins stopped coming, feeling that he might be abusing their hospitality - but they sought him out. He became almost part of the family. In his book The Playfulness of Gerard Manley Hopkins, published in 2008, Fr. Joseph Feeney, S.J. has this to say:

Hopkins' warmest, most enlivening friendship in Ireland was with the MacCabe family of Belleville, D onnybrook, Dublin, headed by Dr. (later Sir) Francis MacCabe, a physician. Hopkins visited them regularly, often for meals and enjoyed playing with the children. Hopkins found them delightfully extrovert people and on Christmas Eve 1885, wrote his brother Everard,

I have friends at Donnybrook, so hearty and kind that nothing can be more so and I think I shall go and see them tomorrow. The MacCabes returned his affection: From the beginning of our friendship we took to him, and he seemed to take also to us. We were very attached to him, and loved his visits. With the MacCabes he was perfectly at home, and talked or kept silent as he felt inclined. His visits were very frequent, mostly spent in my father's study -- He would come about once a week and have lunch with us. My Father and Mother were fonder of him than of any one I can remember coming to the house. He would always bring his clothes to my Mother to mend and it was a labour of love to her.

Hopkins' friendship with the MacCabes covered the entire period of his life in Dublin.

Conclusion

At the end of a long letter to his father dated 17 October 1866, Hopkins says that it is possible even to be very sad and very happy at once. His many friendships in Dublin helped to keep him happy even when he felt sad. One striking feature of his Dublin friendships is the extraordinary diversity in the range of people to whom he became close - the young Jesuit mathematician, Curtis; Stewart, the music professor in Trinity College, Katherine Tynan, the MacCabes and others. No doubt his Dublin friends helped to give his roots rain.

Bibliography

The Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins: Volumes I and II

Correspondence 1852 – 1881 and 1882-1889, Thornton, R. K. R. and Phillips, Catherine (eds.), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013 Volume VII

The Dublin Notebook, Higgins, Lesley and Suarez S. J., Michael (eds.) Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014

Brendan O'Cathaoir (ed.) Holy Redeemer Church, 1792-1992: A Bray Parish, [Fr. Colahan's Diary] Church of the Most Holy Redeemer, Bray, 199

Royal University of Ireland : Calendars 1883 –1889

Secondary Sources

Dictionary of Irish Biography, James McGuire and James Quinn (eds.),

Royal Irish Academy, Cambridge University Press, 2009: articles on:

Arnold, Thomas; Darlington, Joseph; Delaney, William; Finlay, Thomas;

Hopkins, G. M; O'Brien, William; Walsh, Archbishop William; Arnold, Bruce,

Jack Yeats, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1998

Beckett, J. C. , The Making of Modern Ireland 1603-1923, Faber and

Faber, London, 1969 Bebezit, Dictionary of Artists, Grund, Paris 2006

Bergonzi, Bernard, Gerard Manley Hopkins, MacMillan, U K 1977

Connolly, S. J. (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Irish History, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007.

Egan, Desmond The Bronze Horseman Revaluations (Kildare: The Goldsmith Press, 2009)

Ellis, Virginia Ridley, Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Language of Mystery, University of Missouri Press, 1991

Feeney J., S. J., Joseph The Playfulness of Gerard Manley Hopkins, St. Joseph's University of Philadelphia, USA, 2008 --˜Hopkins and the MacCabe Family: Three Children who knew Gerard Manley HopkinsStudies (Dublin) 90 (2001)

Foster, R. F. , W. B. Yeats: A Life, I : The Apprentice Mage 1865 – 1914, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1997

House, Humphry and Storey, Graham (eds), The Journals and Papers of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Oxford University Press, London, 1959

Kitchen, Paddy, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1978

Lahey G. F., S J, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1938 Lyons,

F. S. L. Ireland Since the Famine, Fontana, 1973

Martin, Robert Bernard, Gerard Manley Hopkins A Very Private Life, Harper Collins, London, 1991

Murphy, William M, Prodigal Father The Life of John Butler Yeats (1839-1922), Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London, 1978

Tynan, Katherine, Twenty-five Years: Reminiscences, Smith Elder and Co., London 1913

Tynan, Katherine, Memories, Eveleigh Nash and Grayson, Edinburgh, 1924

White, Norman, Hopkins A Literary Biography, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992.

White, Norman, Hopkins in Ireland, University College Dublin Press. Dublin, 2002

Check out other 2016 Lectures

Hopkins' Mexican Translators

Hopkins Lectures 2016

Hopkins' Dublin Friends

Mexican Translations of Hopkins Poetry

Lectures from GM HOPKINS FESTIVAL 2023

- Vision and perception in GM Hopkins’s ‘The peacock’s eye’ Katarzyna Stefanowicz

Gerard Manley Hopkins’s diary entries from his early Oxford years are a medley of poems, fragments of poems or prose texts but also sketches of natural phenomena or architectural (mostly gothic) features. In a letter to Alexander Baillie written around the time of composition He was planning to follow in the footsteps of the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who had been known for writing poetry alongside painting pictures ... Read more

- Morning's Minion:Hopkins,Trees and Birds Margaret Ellsberg

Margaret Ellsberg discusses Hopkins's connection with trees and birds, and how in everything he wrote, he associates wild things with a state of rejuvenation. In a letter to Robert Bridges in 1881 about his poem “Inversnaid,” he says “there’s something, if I could only seize it, on the decline of wild nature.” It turns out that Hopkins himself--eye-witness accounts to the contrary notwithstanding--was rather wild. Read more

- Joyce, Newman and Hopkins : Desmond Egan

Joyce's friend, Jacques Mercanton has recorded that he regarded Newman as ‘the greatest of English prose writers’. Mercanton adds that Joyce spoke excitedly about an article that had just appeared in The Irish Times and had to do with the University of Dublin, “sanctified’ by Cardinal Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins and himself Read more ...

- Hopkins and Death Eamon Kiernan

An abiding fascination with death can be identified in the writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Easily taken for a sign of pathological morbidity, the poet's interest in death can also be read more positively as indicating, his strong awareness of a fundamental human challenge and his deployment of his intellectual and artistic gifts to try to meet it. Hopkins's understanding of death is apocalyptic. ... As will be shown, apocalyptic thought reaches beyond temporal finality. Hopkins's apocalyptic view of death shows itself with perhaps the greatest consequence in those few works which make the actual event of death a primary concern and which, moreover, leave in place the ordinariness of dying, as opposed to portrayals of the exceptional deaths of saints and martyrs. Read more

An abiding fascination with death can be identified in the writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Easily taken for a sign of pathological morbidity, the poet's interest in death can also be read more positively as indicating, his strong awareness of a fundamental human challenge and his deployment of his intellectual and artistic gifts to try to meet it. Hopkins's understanding of death is apocalyptic. ... As will be shown, apocalyptic thought reaches beyond temporal finality. Hopkins's apocalyptic view of death shows itself with perhaps the greatest consequence in those few works which make the actual event of death a primary concern and which, moreover, leave in place the ordinariness of dying, as opposed to portrayals of the exceptional deaths of saints and martyrs. Read more

Lectures from Hopkins Literary Festival July 2022

- Landscape in Hopkins and Egan Poetry Giuseppe Serpillo

- Walt Whitman and Hopkins Poetry Desmond Egan

- Emily Dickenson and Hopkins Poetry Brett Millier

- Dualism in Hopkins Brendan Staunton SJ Brendan Staunton SJ

- Hopkins Dies in Dublin and is buried in Glasnevin Cemetry Patrick Lonergan

- Gerard Manley Hopkins in Dublin (2012): Michael McGinley

- Hiberno English and Gerard Manley Hopkins's Poetry (2012) : Desmond Egan

Lectures delivered at the Hopkins Literary Festival since 1987

© 2024 A Not for Profit Limited Company reg. no. 268039